After all, Why Not? Why Shouldn't One Man Have All That Power?

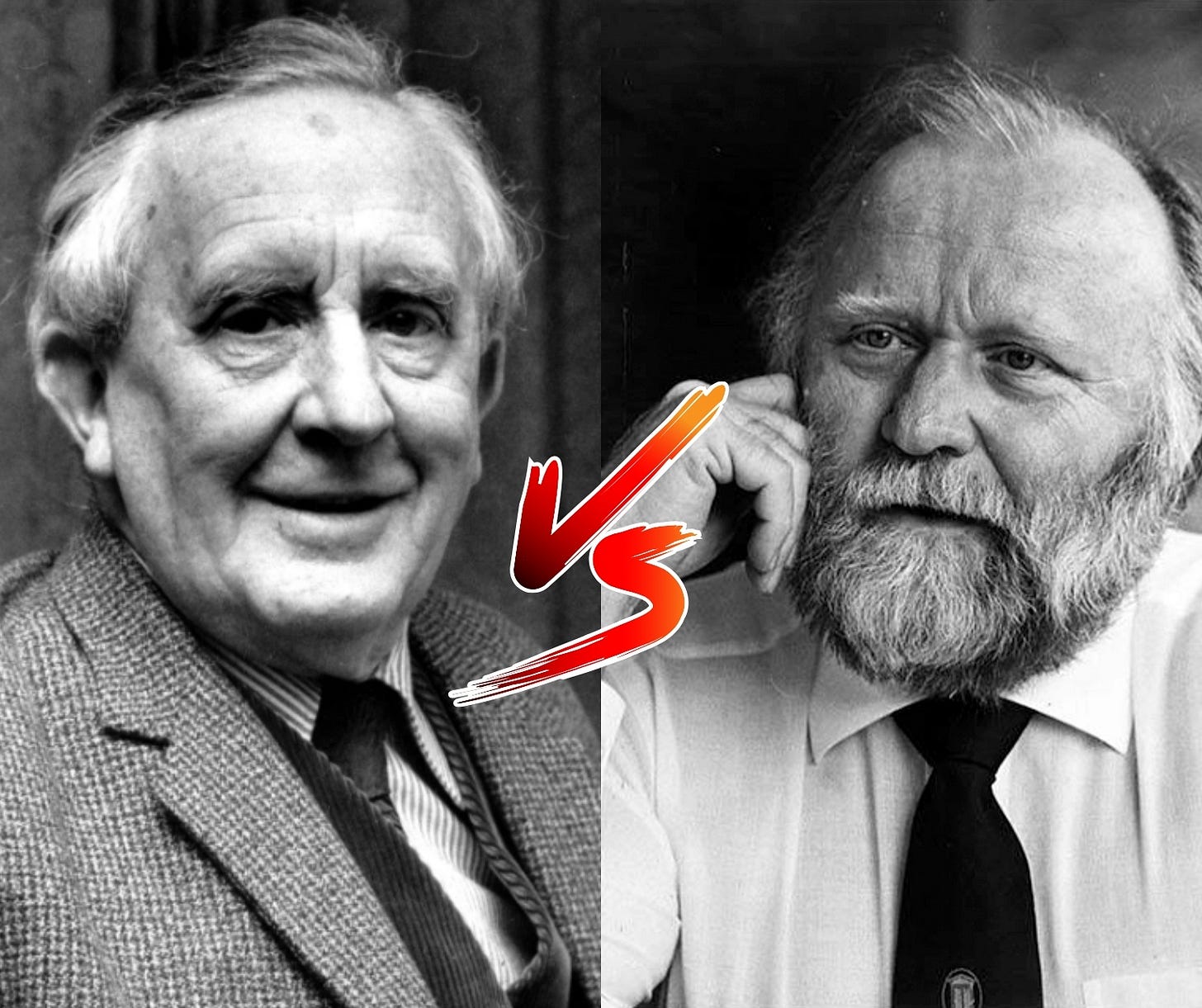

J.R.R. Tolkien vs. Frank Herbert on Power and Corruption

Power tends to corrupt, and absolute power corrupts absolutely—or so Lord Acton, an English Catholic historian and politician, once wrote in an 1887 letter to an Anglican bishop. But is that true? Is it power that corrupts or is it the corrupt who seek power?

Recently I’ve been working on the plot and outline for my science fantasy novel which I’m hoping to begin writing next month (announcing it across my social media presence is my way of painting myself into a corner so I’ll have to actually write it). As I’ve been prepping my plot this year, I’ve been reading and rereading lots of great science fiction and fantasy novels including J.R.R. Tolkien’s the Lord of the Rings and Frank Herbert’s Dune. Rereading these two got me thinking about the authors’ similarities and differences, especially their views on power.

As far as I can tell, both Tolkien and Herbert where limited government type guys who distrusted centralized power and the grinding gears and looming eyes of big government machines which run roughshod over the little guys. But they seem to have come to different conclusions about the nature of power and its potential corrupting influence.

Now as an aside, Tolkien famously disliked Dune, which is regrettable, yet kind of understandable based on what we know of him. I talked with some Tolkien experts about it and they’ve told me that it was probably Herbert’s views on religion which irked Tolkien but I wish he could have taken Dune as an Ecclesiastes-esque, life-under-the-Arrakis-sun-turns-out-poorly-when-no-higher-power-is-running-the-show kind of story, like how Christians are obsessed with Breaking Bad for “portraying evil as evil”. But alas, Tolkien didn’t take Dune that way.

But back to power and corruption. It seems pretty clear from LOTR that Tolkien saw power as a corrupting force and ultimate or absolute power as an assuredly corrupting force which ought to be destroyed for the good of all (Isildur’s Bane/the One Ring/the Ring of Power, Mount Doom and all that). This is a pretty reasonable and straight forward take. Power can corrupt anyone; absolute power will corrupt everyone cursed to possess it. Right? Well, maybe not, because we still have Tom Bombadil, Tom Bombadillo!

Bombadil wasn’t mastered by the ring of power, in fact it looks like just the opposite happened. So this throws just a bit of a wrench into our analysis of Tolkien’s view on power and corruption, but that also makes sense because Bombadil is an enigma within the story as well. So absolute power corrupts almost absolutely? Doesn’t have the same gnomic punch, but still the underlying principle remains, it is power that does the corrupting, when corruption does take place.

Frank Herbert demurs. He says he doesn’t buy that “old saw” (maxim, adage, proverb). Instead, Herbert thought that power attracts the corruptible. He sought to make this point with Paul Atreides in Dune but the point didn’t stick, and it’s actually Herbert’s fault—he made Paul too likable and the odds too grave. It seems more like Paul is a victim of circumstance than a corruptible-turned-corrupted evil dictator. Herbert sought to remedy this in Dune Messiah but again we all just felt sorry for Paul. Then again in Children of Dune and he finally got it right with Alia and maybe with Leto II but then he botched it again with the Golden Path in the end of Children and in the whole of God Emperor of Dune. Leto II is supposed to be space Hitler, a vile dictator, who shows that the corruptible chase power? He literally sacrificed his own humanity to become a sand worm and selflessly guide humanity down the Golden Path in order to avoid a complete and utter species wide extinction. He played the part of the hated Emperor for the sake of humanity, taking up the reigns that his father as too tired or weak to take up, and he secured a better future for all of the human race. Now you may still hate him, but the God-Emperor of Dune is at least a complicated figure, one who doesn’t neatly fall under “corruptible man seeks power for power’s sake”. Herbert fails again—even though his failure produced fantastically complex characters and wonderful stories. With that said, I do think Herbert’s notion has merit even if he failed to demonstrate it in his novels (barring the case of Alia). There’s something corrupted in those who seek power, especially those who seek power for power’s sake.

(Below is Herbert in his own words on power alluring the corruptible)

So then, who’s right? Does power corrupt and absolutely so? Or is it a kind of observer bias? We see all these corrupt individuals with power and think, “man, that power stuff is corrupting, huh?” but in reality, we’re just looking at the victors, those who have won power, and those who would seek power in the first place are those who are inherently corruptible. Thus, it’s not power’s fault, but the corruptible people seeking it who are to blame. This is reminiscent of one of the major problems with Plato’s idea of the philosopher-king. Societies won’t flourish properly until kings become philosophers and philosophers become kings—but a philosopher would never want to be king and if a king became a philosopher maybe he’d likewise reject the position outright after being enlightened to the nature of power.

Can I say that the true answer probably lies somewhere between Tolkien and Herbert? I hate to do it, it’s very cliché but there probably is a golden mean between these two ideas. You have to be corruptible to be corrupted, that’s obvious. So anyone who would be corrupted by power, absolute or otherwise, started off as corruptible. But if we’re all corruptible, then the only kinds of people who can seek out power are likewise going to be corruptible and then will be corrupted by power once they get it. I think that we are all corruptible as a matter of fact, so I think this is the case. But I tend to agree with Herbert that those who are actively striving after power, those who are clawing and scratching and fighting to get their hands on the reigns, are generally corrupted already, rather than merely corruptible—they’re probably psychopaths. The person most desperate for power is the one we should keep farthest away from it. However, if you foist an immense amount of power on someone not seeking it, surely it can still wreck them, right? We’ve seen this with princes. They’re not necessarily seeking power, or at least not all of them are, but it is bestowed on them nonetheless due to ‘birthright’. The coronation happens and over time the power goes to their head and they are corrupted into a tyrant king.

So, here’s where I think I’m going to land the power plane: every human being this side of Adam is corruptible; power tends to corrupt; absolute power corrupts fallen human beings absolutely and it allures the psychopaths. The one who is most desperate for power is the one who should be kept furthest from the reigns.

But what do you think?

Love this, but worth wondering how the systems within which power operates can either mitigate or exacerbate corruption (something Tolkien explores deeply in his writings).

Love this look at power and corruptibility. I wonder, too, if those who stick to their values inherently tend to be denied power, also--by being unwilling to compromise. It seems to me that often the moral man (or woman) who stands on principle often suffers for it, rather than being rewarded for it. But I guess that's another question, too: who does society reward power to, and why? Thanks for sharing! This will definitely be floating around in my head all day. ^_^