C.S. Lewis's 6 Sub-Species of Science Fiction

C.S. Lewis is known as many things, but he’s perhaps least known by most as a science fiction aficionado and critic. But he was both. In his essay “On Science Fiction” (originally given as a talk to the Cambridge University English Club on Nov. 24th 1955), Lewis carves the species ‘Science Fiction’ (SF) into at least 6 sub-species, some of which he enjoyed and others which he did not. He starts by critiquing a kind of pseudo-SF first, then moves on up from his least favorite to his favorite SF sub-species.

Do these sub-species sufficiently carve up the SF genre as we know it today? Probably not—he wrote this in 1955 (!), but they’re still helpful for modern SF enjoyers to utilize and perhaps even update, and certainly his analysis should be interesting to CSL buffs. So, let’s get on with ‘em! But let me just note that Lewis didn’t give names to each sub-species so I had to come up with all but the first 2, so if there’s poor nomenclature, it’s my fault and not Lewis’s.

And just one more note, I’m not sure that Lewis intended these to be mutually exclusive and collectively exhaustive. I think he recognized there were other sub-species—and I know he recognized that there are other sub-sub-species since he says as much (acknowledging that SF’s Aristotle has not yet come to fully categorize the logical space of all SF). Lewis’s own SF trilogy, the Ransom Trilogy (not “space trilogy” his whole point was to reconstrue ‘space’ as ‘heaven’) seems to fit in multiple sub-species (Out of the Silent Planet and Perelandra might also fit under Speculative Travel SF and That Hideous Strength might equally fit under Eschatological SF, though Lewis seems to only put them under Mythopoeic SF). Okay, now let’s really get on with ‘em!

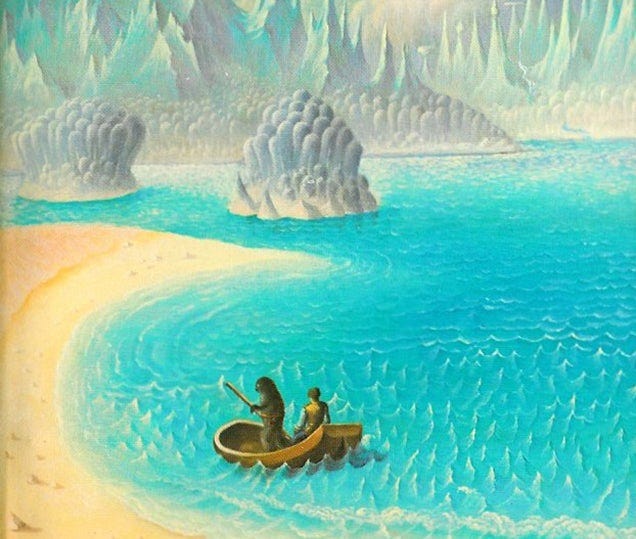

(A beautiful cover for Lewis’s Out of the Silent Planet)

(i) Fiction of The Displaced Persons

Lewis disliked this sub-category the most. According to him, authors of this brand are just telling ordinary stories in an SF setting without using the SF setting, tropes, or machines, to do any of the lifting. In this sense, they’re pseudo SF rather than genuine SF. Think of a love story set 1,000 years into the future which sets the stage as an SF story but never uses any SF to impact the story. These stories could be written in the present age without the unnecessary time-jump, but they’re written by ‘displaced persons’, commercial authors who don’t really want to write SF but want to capitalize on the popularity of the genre. Lewis condemns these stories for “leap[ing] a thousand years to find plots and passions which they could have found at home.”[1]

(ii) SF of Engineers

Lewis describes this sub-species of SF as being written by authors who are primarily interested in giving plausible depictions of space-travel, or some other SF theme, which isn’t impossible in-principle. They’re interested in giving their best guesses as to how scientist might actually bring these potentialities into actualities, in an imaginative way and inside a story. Lewis cites Jules Verne’s Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea, H.G. Wells’s Land Ironclads, as well as Arthur C. Clarke’s Prelude to Space. Lewis respected this sub-species, but didn’t “have the slightest taste” for them. He notes that the original appeal of these works is altered by the coming of the real thing, i.e., the invention of submarines and tanks in the case of Verne and Wells books cited above.

[A little excursus: I think we might also refer to this sub-species as “Hard SF”, that is SF which is scientifically accurate but for one element. The contrary would be “Soft SF” which is much looser with scientific facts and is more concerned with characters and plot. Many point to Larry Niven’s Ring World as a quintessential Hard SF story.]

(iii) Speculative Travel SF

Lewis describes this sub-species of SF as scientific but speculative, it’s a more developed form of what scientists naturally do already when describing places that no humans have ever gone before. So before any humans traveled to the moon, scientists would use the information they had to give descriptions of what it might be like to experience walking on the moon, listing the probable effects on the senses of the human observers. The SF author just takes this process to a much deeper level, according to Lewis. Lewis finds a long tradition of Speculative Travel SF going back to Homer who asked “what would Hades be like if you could go there alive?” and then gives his own speculative answer by sending Odysseus there in the Odyssey.[2]

In contrast to SF of Engineers, the mechanics of the journey doesn’t matter as much as the depiction of the qualitative experience of the new world or place. Furthermore, Lewis argues that character development is likewise not key for the success of such stories. The focus is truly on what it would be like for a human being to experience this new place, and that’s enough.

Lewis says he respects this sub-species and says it is capable of many virtues but warns that “it is not a kind which can endure copious production.”[3] The first or second trips to the Moon and Mars set the stage for the rest and “it becomes difficult to suspend our disbelief in favor of subsequent stories [,] However good they were they would kill each other by becoming numerous.”[4] Now I think I disagree with Lewis here, partially because I want him to be wrong. I’d like to think that I could still write a golden age of SF style story about traveling to the moon and I could pitch a different experience than the old timers wrote about—and different still than the astronauts who walked on the moon [we could just stipulate that the moon landing was fake and boom, wholly new experiences abound]. But I need to chew on this more because it’s not an easy thing to disagree with CSL.

(iv) Dystopian SF

In critiquing the first sub-species, Fiction of the Displaced Persons, Lewis notes that while commercial authors abuse time-jumps by employing them but never following up on them, there are legitimate uses of the “leap into the future” machine (and here Lewis has the neo-classical notion of ‘machine’ in mind, e.g. deus ex machina— a plot device rather than a modern sense of metal ‘machine’—he’s not literally talking about a time travel machine but the method of setting your story into the future). Lewis says that legitimate uses of the time-jump machine include satire and prophesy. For satirical dystopian SF, think of the movie Idiocracy which lambasted the society of 2006 by projecting the abuses of its trends 500 years into the future (although it was originally intended as satire, it’s unfortunately turning into prophecy day by day). For prophetic dystopian SF, Lewis lists Huxley’s Brave New World and Orwell’s 1984. [Another excursus: Lewis has a great essay on Orwell where he compares and contrasts his 1984 with his Animal Farm and argues that “The shorter book [Animal Farm] does all that the longer [1984] does. But it does more. Paradoxically, when Orwell turns all his characters into animals he makes them more fully human.”[5]]

(v) Eschatological SF

Lewis found another use of the time-jump machine which is different from Dystopian SF, that is, Eschatological SF, or end times SF. While Dystopian SF is about a future of humanity based on political or social trends or ideologies, Eschatological SF is about the ultimate destination of the human species. Here he gives Well’s Time Machine as an example (here the neo-classical ‘machine’ and the modern ‘machine’ are one). In this sub-species, authors will often give pseudo-histories of the human race and may step off the typical notion of a ‘novel’. These stories are meant to give us a collective memento mori for our human race. Lewis says, “if memento mori is sauce for the individual, I do not know why the species should be spared the taste of it.”[6]

Apparently, in the 1950s, some folks thought stories of this sub-species where escapist and somehow fascist, I don’t know why, but Lewis defends them by giving an analogy of stewards on a ship. Say a bunch of stewards are protesting on the ship they’re meant to be working, there’s a whole heated debate, passengers are getting angry, management is upset, it’s a mess. Lewis says one could imagine the chief spokesman of the stewards being angry at anyone who snuck away from the debates to get a breath of fresh air out on the upper deck. But this person might get a new perspective on the debate by being reminded of the vastness of the ocean, the smallness of the boat, and the insignificance of their current trials in the grand scheme of the cosmos. That’s what this sub-species of SF is meant to offer: perspective. And to those who claim its sheer escapism, Lewis quotes his friend J.R.R. Tolkien, from their own personal correspondence, as asking him “what class of men would you expect to be most preoccupied with, and most hostile to, the idea of escape?” to which Tolkien himself answered “jailers”.[7]

(vi) Mythopoeic SF

Mythopoeic or fantastic SF was Lewis’s favorite. He gave a nod to the old American pulp magazine, Fantasy and Science Fiction, as being the best on offer because it included mythopoeic stories, i.e., space-travel stories alongside stories of gods, ghosts, ghouls, fairies, demons, monsters, etc. These kinds of stories deal in myth-making and myth-building. They may use pseudo-scientific machines (again the neo-classical sense) merely satisfy our critical intellects but Lewis argues that perhaps it’s best to utilize supernatural machines—a lesson he said he learned between writing Out of the Silent Planet (where a space ship brings Ransom to Mars) and Perelandra (where an angel carries Ransom to Venus in a casket made of ice). This mythopoeic sub-species of SF ought to be judged by the same standards as all other mythopoeia, it’s merely an SF incarnation of that broader phenomena, it’s “an imaginative impulse as old as the human race working under the special conditions of our own time.”[8]

Mythopoesis is easier to accomplish the less human beings know about their own world, but as geographical knowledge grows, it becomes harder and harder to hide your myths in an unexplored forest and explore strange new regions with new marvels. Thus, mythopoeic SF takes its readers to new worlds, where the “wonders, beauty, or suggestiveness” are in full focus, and where old myths are reconfigured or remade and new myths are crafted. Here, scientific probabilities aren’t as important as wonder, beauty, and mythos [we might consider this ‘soft’ science fiction].

Lewis says that Jung went he farthest in trying to explain why myths run so deep in the human psyche, but he goes on to say that Jung ultimately failed and ended up producing yet another myth himself. But for the reader who’s doesn’t have a firm grasp on what Lewis means by mythopoeic SF, think of something like SF stories which incorporate Jungian archetypes but perhaps deeper and richer than Jung acknowledged (?); SF stories with deep mythological structure. Lewis argues elsewhere (in his review of Tolkien’s The Fellowship of the Ring) that mythopoesis runs deeper than allegory, for in myth “There are not pointers to a specifically theological, or political, or psychological application. A myth points, for each reader, to the realm he lives in most. It is a master key; use it on what door you like.”[9] It is as such that Lewis describes mythopoeia as “not the most, but the least, subjective of activities”.[10]

Lewis explains that while writing his Out of the Silent Planet he was already aware that the telescopes of his time had disproved the notion of deep canals on Mars as a mere optical illusion but the canals already existed in the Martian myth in the minds of the public and thus were fair game to include and expand in his own Martian mythopoesis.

Lewis warns the reader that under this sub-species, sub-sub-species are bound to explode, including the sub-sub-specie of intellect free of emotion SF, to which he points to Abbot’s Flatland; Farcically Impossible SF like F. Anstey’s Brass Bottle; Moralistic Impossible SF which is meant to convey a moral truth or lesson, like Stevenson’s Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde; and Marvelous SF which is not meant primarily as a comment on life, like many of the others, but instead is meant to be an addition to it. Here, Lewis gives Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings and David Lindsay’s A Voyage to Arcturus as examples.

So there you have it, Lewis’s 6 sub-species of SF and a few sub-sub-species. Like I said above, I think Lewis’s own SF might fight under a few sub-species, but it’s clear that he would place his Ransom trilogy under Mythopoeic SF. He’s probably right and I’m probably wrong, but read the trilogy for yourself and let me know what you think! Grab them here from my affiliate links to support my work and if you liked this post then consider becoming a paid subscriber and help me justify doing more of these: Random Trilogy

[1] C.S. Lewis, “On Science Fiction” in C.S. Lewis: Essay Collection & Other Short Pieces, 453.

[2] Ibid., 453.

[3] Ibid., 455.

[4] Ibid.

[5] C.S. Lewis, “George Orwell” in CSL Essay Collection & Other Stories, pg. 565

[6] C.S. Lewis, “On Science Fiction” in C.S. Lewis: Essay Collection & Other Short Pieces, 455.

[7] Ibid., 456.

[8] Ibid., 455-6.

[9] C.S. Lewis “Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings” in CSL: Collected Essays, pg. 521.

[10] Ibid., 522.

Of course Lewis loved Animal Farm more than 1984, for Lewis always loved good stories with animals more than those without. Or so I say tongue in cheek. ;)

Distopyan might be accompanied more generally by Anthropological SF: using the vastness of future and space as a broader canvas to depict humand and societal aspects. 'Three Body Problem' and 'Dune' are examples of the most political/sociological, and Cordwainer Smith's stories an example of the more psychological side.

Distopyan or Anthropoligical can both degenerate into Fiction of the Displaced Persons if done incorrectly.