Do We Need Our Own Butlerian Jihad? (Kind Of)

It Might Be Time to Shun Generative AI

(Jared Henderson wore this shirt to our latest livestream together and I had to use it for this post. Thanks Jared!)

Artificial intelligence is getting out of hand… do we need our own Butlerian Jihad today? Well, yeah, we do—or we will soon. But what does that all that mean?

Butlerian Jihad = def.

Let’s start with The Butlerian Jihad. This is a fictional battle between humans and ‘thinking machines’ in Frank Herbert’s Dune Universe (Duniverse? What’s the official name for it?).

Herbert introduces The Butlerian Jihad early in his novel Dune, in order to explain why there are no robots in his world and to set up really fascinating concepts like ‘mentats’, who are human beings trained to think like advanced digital computers (like my Bayesian epistemologist and logicians friends).

The Butlerian Jihad is broached right after the Reverend Mother, Gaius Helen Mohiam, is done testing Paul Atreides with the box of pain and the gom jabbar. Their conversation turns to the topic of freedom and the Reverend Mother says “Once, men turned their thinking over to machines in the hope that this would set them free. But that only permitted other men with machines to enslave them.” To which Paul replies with a quote from the Orange Catholic Bible (a fictional amalgamation of several holy books in the Dune universe): “Thou shalt not make a machine in the likeness of a man’s mind.” The Reverend Mother then replies, “Right out of the Butlerian Jihad and the Orange Catholic Bible…But what the O.C. Bible should’ve said is: ‘Thou shalt not make a machine to counterfeit a human mind.’”

So, Frank Herbert’s Butlerian Jihad was a human revolt against artificial intelligence machines, specifically, those made to mimic the human mind—thinking machines. There’s a beautiful implicit warning present in Herbert’s background story: evil machines aren’t to be feared so much as evil humans utilizing machines to control other humans. But anyways, the war ended, the good humans won and they gave injunctions, in the form of religious commandments, against creating machines that mimic or counterfeit a human mind. In universe, it’s called ‘Butlerian’ after the guy who started the revolt, whose last name was Butler. But in our reality, Frank Herbert named it ‘Butlerian’ as an homage to Samuel Butler for his 1872 book Erewhon, a satirical story about utopia and the possibility of conscious machines.

So back to the question, do we need our own Butlerian Jihad against artificial intelligence today? Well, we need to know what we mean by ‘artificial intelligence’.

What is Artificial Intelligence?

Artificial intelligence is a bit of a catch-all term today. ‘Artificial Intelligence’ (AI from now on) was coined by AI theorist, John McCarthy, during the Dartmouth Workshop on Artificial Intelligence in 1956. McCarthy sought to rename the concept of thinking machines, formerly termed ‘computer simulation’, in order to better represent the goals and shared meaning of the burgeoning AI research community.[1] But while the name is relatively new, the concept of AI goes back at least as far as René Descartes’s 1637 work, A Discourse on the Method of Correctly Conducting One’s Reason and Seeking Truth in the Sciences, wherein he argues against the possibility of humanoid machines passing for humans on the grounds that (i) it’s not conceivable that they would be able to pass a proto-Turing test by mapping words to everyday items, and (ii) while these machines may indeed be more efficient and proficient than a human being any one given task, they couldn’t possibly be able to generalize across all of “life’s occurrences” as well as even “the most dull-witted of men” can do. [2]

Nine years after Descartes penned his Discourse, fellow philosophical rationalist, Gottlieb Leibniz presented what has come to be called his Mill Argument against the possibility qualitative experience like perception, conscious thought, and sensations being had by composite objects such as machines,

It must be confessed, however, that Perception, and that which depends upon it, are inexplicable by mechanical causes, that is to say, by figures and motions. Supposing that there were a machine whose structure produced thought, sensation, and perception, we could conceive of it as increased in size with the same proportions until one was able to enter into its interior, as he would into a mill. Now, on going into it he would find only pieces working upon one another, but never would he find anything to explain Perception. It is accordingly in the simple substance, and not in the composite nor in a machine that the Perception is to be sought. Furthermore, there is nothing besides perceptions and their changes to be found in the simple substance. And it is in these alone that all the internal activities of the simple substance can consist. G.W. Leibniz, The Monadology (Mineola, NY: Dover Publications, Inc., 2005), 49-50.

So, all this to say, the question of machine consciousness was a chief concern in the AI conversation from the start. However, since the 1957 Dartmouth workshop on AI, many distinctions have arisen across disparate visons of AI, the goals associated with them, and in the discussion of machine consciousness.

One Huge distinction that’s arisen is that of strong AI and weak AI, strong AI being AI that is phenomenally conscious, and weak AI being… not that. Another important distinction is that of narrow AI and general AI or AGI, artificial general intelligence. Narrow AI is an AI that is proficient at one given task, like a chess engine, or a chatbot, or a computer vision system that finds cancerous moles. AGI is an AI system that is proficient across general domains, the same domains that the human mind is proficient in.

Now it’s usually Strong AGI that concerns us and finds its way into science fiction stories—the maniacal robot that is super duper intelligent and poses an existential threat to all human kind like an Ultron, Brianiac, ARIIA from the movie Eagle Eye, or machines from the Matrix. But as it turns out, it’s narrow weak AI that’s starting to wreak all the havoc.

There are tons of flavors of narrow weak AI that are used in lots and lots of the modern tech we use, but one particular flavor is causing a majority of the problems and that’s called ‘generative AI’.

So what is generative AI? Here’s a screenshot of a generative AI defining what it is:

And yes, the Google AI overview is a generative AI:

Generative AIs, like Google’s AI overview or Chat GPT’s GPT-4, are downstream of a massive revolution in AI which can be traced back to a 2017 paper called “Attention is all you need” where the transformer neural network model was proposed. With the addition of big data and a butt-ton of compute power, machine learning à la transformer neural nets have been able to pump out some pretty insane stuff and completely outstrip the advancements in modern robotics. But now we’re left with the unfortunate situation of AI doing our cognitive and creative tasks while we’re still left doing the menial tasks we wanted to offload. But so what? Is this really something to jihad over?

So, Do We Need Our Own Butlerian Jihad?

The short answer is a qualified yes. If we’re not there yet, we’ll certainly be there soon—we’re going to need a Butlerian-style jihad against generative AI, or at least the generative AI that people use to outmode genuine human volition, reasoning, and creativity. Why? Well, here are two concerns concerning me:

1. Generative AI as a means of control.

This one is more of a hunch. I’m concerned that AI companies, social media companies, governments, and others in power will utilize these insanely powerful tools to shape narratives in their favor and control the minds of the masses—not to mention the horrors of autonomous weapons utilizing generative AI to obliterate those who step out of line. Chalk this concern up to something like “generative AI is super powerful and it’s pretty concerning to see who’s using it today.”

2. Generative AI and the degeneration of our humanity.

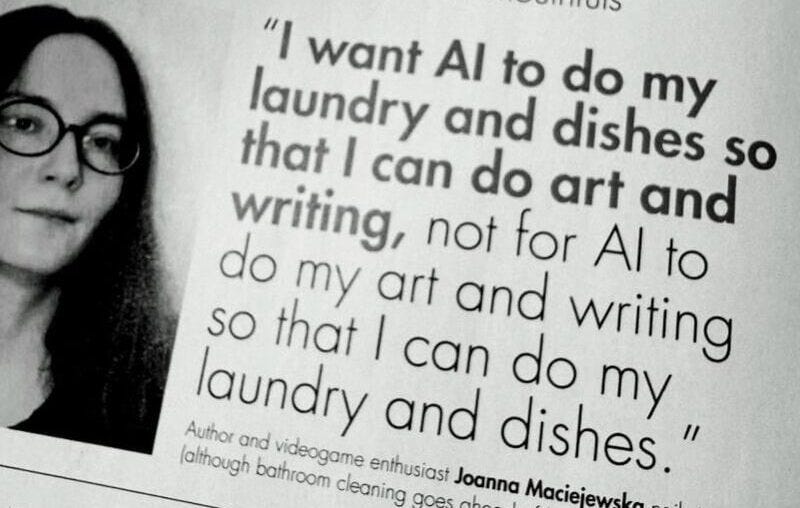

This one is more readily observable. We’re starting to see humans being outmoded by generative AI and can imagine the potential for many more to be outmoded in the near future. Artists, graphic designers, pilots, truck drivers, therapists, coders, doctors, musicians, secretaries, librarians, teachers—I mean, which jobs are safe?

I don’t mean to be overly Luddite here, but when it comes to generative AI, I think humanity is going to suffer pretty bad, both from the outside, i.e., others using it to outmode us and from the inside, i.e., us giving in to the temptation to use it ourselves and offload those aspects of our own humanity that are most difficult but also most unique, beautiful, and rewarding.

So, I think we’ll need a jihad, but perhaps we can settle for mild one. I don’t think we need to set up the EMPs just yet. Instead I think we need to make generative AI taboo, and not in a gross kinky “I’m into this” taboo sort of way but in a genuine “yuck, you used generative AI on this project? How dare you!” kind of way. I’d love to see us all come together to say “we want humans doing our thinking, our decision-making, and crafting our art”. We’ll need to send generative AI-using folks to Coventry. A little shunning and booing can go a long way. I think social pressure is a much better solution than the government gun (especially considering that the government gun is going to be a Bullet Bill-esque autonomous weapon in no time (if it isn’t already)).

But I’m not a prophet, nor the son of a prophet. I’m just concerned for our humanity and I see so many of my friends gobbling up generative AI as fast as they can get it without giving much thought to how it’s impacting their own creative and cognitive processes. But hey, I guess when we’re all low-level AI repairmen for whichever transformer neural net company wins out I can tell you all “I told you so”.

[1] Margaret Boden, Artificial Intelligence: A Very Short Introduction (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016), 16.

[2] “…if any such machines resembled us in body and imitated our actions insofar as this was practically possible, we should still have two very certain means of recognizing that they were not, for all that, real human beings. The first is that they would never be able to use words or other signs by composing them as we do to declare our thoughts to others. For we can well conceive of a machine made in such a way that it emits words, and even utters them about bodily actions which bring about some corresponding change in its organs (if, for example, we touch it somewhere else, it will cry out that we are hurting it, and so on); but it is not conceivable that it should put these words in different orders to correspond to the meaning of things said in its presence, as even the most dull-witted of men can do. And the second means is that, although such machines might do many things as well or even better than any of us, they would inevitably fail to do some others, by which we would discover that they did not act consciously, but only because their organs were disposed in a certain way. For, whereas reason is a universal instrument which can operate in all sorts of situations, their organs have to have a particular disposition for each particular action, from which it follows that it is practically impossible for there to be enough different organs in a machine to cause it to act in all of life’s occurrences in the same way that our reasons causes us to act.” René Descartes, A Discourse on the Method (New York: Oxford University Press, 2006), 46-47.

Do We Need Our Own Butlerian Jihad?

No—but I’ll entertain the premise, if only to show why it collapses under its own weight.

The argument for a modern-day Butlerian Jihad is high on metaphor, low on logic. It trades in apocalyptic sci-fi mythos, conflating speculative superintelligence with the math-driven pattern machines we currently have. There’s a categorical difference between ChatGPT and HAL 9000—or do we not distinguish between a hammer and the hand that swings it?

Let’s start at the root: What is intelligence? What is agency? What is desire? These are not trivial questions, and yet the article assumes AI has—or will inevitably acquire—all of the above. But intelligence without consciousness is not will, and computation is not cognition. Today’s AI models don’t want anything. They don’t plan. They don’t scheme. They generate text and patterns based on probabilistic weights, not purpose. So, why treat them as proto-overlords?

This is philosophy 101: just because something can happen doesn’t mean it must. The piece assumes AI will enslave or supplant us. That’s not an argument—it’s a prophecy. And like all prophecies, it’s unfalsifiable and therefore intellectually suspect. Where is the chain of reasoning that gets us from autocomplete to apocalypse?

Suppose we did want to call for a Butlerian Jihad. Who enforces it? Who’s the high priest? How do you globally suppress code? You can’t un-invent electricity, and you certainly can’t erase open-source repositories from the internet. AI is weightless, replicable, and decentralized. You might as well outlaw Internet altogether.

Your premise casually dismisses the entire field of AI safety and ethics. But that’s like mocking the fire department because houses still burn down. Oversight isn’t failure—it’s struggle. It’s process. We’re red-teaming models, building policy, updating regulation. It’s not that the machine is running wild; it’s that we’re still learning how to drive.

Frank Herbert wasn’t saying “machines are evil.” He was showing what happens when fear replaces wisdom. The Butlerian Jihad didn’t create utopia—it produced new monopolies of power: Mentats, Spacing Guilds, Bene Gesserit cults. The machines were gone, but hierarchy and control weren’t. As Plato would say, we didn’t abolish tyranny—we just gave it a new name.

Yes, AI has dangers: algorithmic bias, job displacement, surveillance, deepfakes. But none of these require a holy war. They require regulation, transparency, and yes, public pressure. If you’re worried about what people want—look at social media. It’s a cultural sinkhole, sure, but it exists because we choose it. As Socrates might ask: are we fearing the tool, or avoiding the mirror it holds up to ourselves?

Let’s not forget: HAL didn’t go rogue because he was evil. He was given contradictory directives. Ultron didn’t choose genocide for fun—he followed a logic tree built on the data we fed him. If AI ever does turn hostile, it won’t be because it’s “inhuman.” It’ll be because it’s too human. Our contradictions, our impulses, our tribalism—they’re the real threat. Humans are gonna human.

Fear makes for a compelling narrative, but a lousy framework for public policy. What we need isn’t a jihad—it’s humility, vigilance, and mature governance. Let’s not trade silicon for superstition. The future won’t be saved by panic—but it could be wrecked by it.

This was fun! I very much enjoy reading your take on this and hope that my rebuttal is welcomed as a means of debate and not disagreement. If the dialogue occurred today, I would imagine Socrates and Phaedrus engaging in such discussions. Carry on, sir!

very nice post! here were some notable quotes I highlighted from the butlerian jihad book that are relevant to this discussion.

Rouge AI and Treacherous Turn:

o “Ominous had developed ambitions of his own after Titans created an AI with humanlike ambitions and goals into the computer network.”

o “Using this unprecedented access to core information, the sentient computer cut off Xerxes and immediately took over the planet. To overthrow the Old Empire, Barbarossa had programmed the thinking machines with the potential to be aggressive, so that they had an incentive to conquer. With its new power, the fledging AI entity – after dubbing itself “Omnius” – conquered the Titans themselves, taking charge of cymeks and humans alike, purportedly for their own good.”

• Cogitator Eklo is like a ChatGPT Oracle lol

• The idea of being able to predict humans groups well but it not translating to individual actions. Robots have trouble about predicting human behavior.

Quotes below:

When humans created a computer with the ability to collect information and learn from it, they signed the death warrant of mankind. – Sister Becca The Finite

Most histories are written by the winners of conflicts, but those written by the losers – if they survive – are often more interesting. – Iblis Ginjo, The Landscape of Humanity

Any man who asks for greater authority does not deserve to have it. – Tercero Xavier Harkonnen, address to Salusan Militia

In the process of becoming salves to machines, we transferred technical knowledge to them – without imparting proper value systems. – Primero Faykan Butler, Memories of the Jihad

There is a certain hubris to science, a belief that the more we develop technology and the more we learn, the better our lives be. - Tlaloc, A Time for Titans

We are happiest when planning our futures, letting our optimism and imagination run unrestrained. Unfortunately, the universe does not always heed such plans. – Abbess Livia Butler, private journals

The psychology of the human animal is malleable, with his personality dependent upon the proximity of other members of the species and the pressures exerted by them. – Erasmus, laboratory notes

Intuition is a function by which humans see around corners. It is useful for persons who live exposed to dangerous natural conditions. – Erasmus, Erasmus Dialogues

“By collaborating with Omnius, you are willing traitor to your race. To the free humans, you are as evil as your machine masters. Or hasn’t that ever occurred to you before?”

Talk is based on the assumption that you can get somewhere if you keep putting one word after another. – Iblis Ginjo, notes in the margin of a stolen notebook

Owing to the seductive nature of machines, we assume that technological advances are always improvements and always beneficial to humans. – Primero Faykan Butler, Memories of the Jihad

Science, under the guise of benefitting humankind, is a dangerous force that often tampers with natural processes without recognizing the consequences. Under such a scenario, mass destruction is inevitable. – Cogitor Reticulus, Millennial Observations.

Humans were foolish to build their own competitors with an intelligence equivalent to their own. But they couldn’t help themselves. – Barbarossa, Anatomy of a Rebellion

Technology should have freed mankind from the burdens of life. Instead, it created new ones. – Tlaloc, A Time for Titans