G.K. Chesterton's Transcendental Mystic Influence on C.S. Lewis

That's a Mouthful but I'll Try to Explain

As I’ve announced on previous posts, we’re doing a read-along and book club on C.S. Lewis’s deepest philosophy/theology book, Miracles. We’re going to be reading through it together in 6 weeks and I’m committed to writing at least 6 companion essays to help us all think through Lewis’s arguments—it’s pretty tough stuff. I’m also planning on adding at least 2 more essays, one on CSL as philosopher and one on CSL’s argument from reason—which I will cover in the essay on chapters 3-6 but which I want to nerd out on way more so I’ll probably make an entire essay on it.

So, all of that is the read-along. You grab a copy of the book, keep up with the reading schedule. Read my companion essays, and comment on the posts with your own thoughts and questions and talk with me and others who are reading along at the same pace. It’s going to be awesome! And it’s open to everyone, the essays are free to read right here on my Substack.

HarperCollins heard about our read-along and offered to send 10 copies to my audience for free! We ran a giveaway and I just DM’d the winners yesterday. So, congrats to the winners! Those books will go out this week.

As for the book club, we’re doing 3 Zoom call session during our read along schedule. That’ll be open to any and all of my paid subscribers here on substack, or on Patreon, or YouTube members—for all of my projects. If you’re supporting my financially then you’re in! And I’m going to record those sessions and send them out for paid subscribers as well. Check out all the details and the read-along schedule in this post here:

We're Doing a Read-Along on C.S. Lewis's Miracles!

The read-along/book club on C.S. Lewis’s Miracles is a go! In my last post I put out my feelers to see if my audience would be interested in doing a read-along after seeing how many folks continue to be blessed by Jared Henderson’s read-alongs on his Substack. It turns out, people really, really love C.S. Lewis and would love to do a read-along on his stuff—who woulda…

But what does any of this have to do with G.K. Chesteron’s transcendental mysticism? Well, I’ve been preparing my companion essays for Lewis’s Miracles and I’ve been reminded of many of CSL’s influences, especially those influences which helped to shape his argument(s) from reason, which he puts forth in chapters 3-6 & 13. The biggest influences on the argument(s) from reason were philosophers Arthur James Balfour and Elizabeth Anscombe—and like I said, I’m planning at least one big deep diving bonus essay covering that. But another massive influence on CSL is G.K. Chesterton, both in general and specifically on Lewis’s args. from reason.

Chesterton was CSL before CSL. He was a British public intellectual who wrote fiction, poems, and incredibly erudite and winsome essays. He was about a generation older than CSL, being born in 1874 and passing away in 1936, whereas CSL was born in 1898 and passed away on November 22nd, 1963—the same day as JFK and Aldus Huxley.

Chesterton served as an exemplar for CSL on what a Christian public intellectual could and should look like, but he also influenced the content of CSL’s Christian world-and-life-view.

There is a plethora of places where we can find Chesterton’s influence on CSL’s thought but I want to point to just one place, as it pertains to one of CSL’s formulations of his argument from reason, a kind of transcendental presentation.

Now what on earth does ‘transcendental’ mean?

Medieval philosophers understood the ‘transcendentals’ like truth, goodness, oneness, etc. as explications of ‘being’, they were the properties of being, or maybe even perspectives on the concept of ‘being’. These are ‘common notions’ which transcend all other categories—but not in the sense that they are beyond all categories and thus not related to them, but rather, the transcendentals, as properties of ‘being’ itself, are diffused (so to speak) throughout all the other categories existence.[1]

I get that this can be a bit confusing for modern minds to get. We don’t think much about ‘being’ (ens) nowadays—thanks in part to Immanuel Kant, who argued against ontological arguments for God by claiming that ‘existence’ is not a predicate, that is, saying “thing x exists” doesn’t really add anything to the statement since, according to Kant, “exist” isn’t a quality which we can use to describe something. Now pre-moderns might have said something closer to “thing x participates in being” rather than “thing x exists” but the notion is the same and it was this notion that Kant took aim at.

Ironically, Kant took the word ‘transcendental’ from the Medieval conception of being and applied it to a kind of argument he was fond of: transcendental deductions. Transcendental deductions indirectly deduce things which must exist based on some aspect of our human experience. It’s an indirect process in that we’re not directly looking at the thing-in-and-of-itself (indeed we never can get to the thing-itself for Kant), but we’re deducing its existence (for lack of a better word) from things or phenomena which necessarily depend on that thing undergirding it.

Here’s an analogy: you’re walking on a wood floor in a building you’ve never been in before. You can deduce that there are floor beams under the wood floor and a foundation beneath that from the fact that you’re walking on the floor—it must be the case, even though you’ve never seen them. You know the beams are there there since you wouldn’t be able to have this experience of walking on the floor if they weren’t there (this analogy comes from Cornelius Van Til).

That’s the kind of thing that Kant is doing with his transcendental deductions, like when he transcendentally deduced the self (the ‘I think’) from his own experiences and likewise the unity of the self’s consciousness (the transcendental unity of apperception).

So, Kant tried to put down the Medieval talk of ‘being’ and ‘existence’ even while pillaging their concept of ‘transcendental’ for his own deductions. After him, other philosophers picked up the transcendental method of reasoning and called their arguments ‘transcendental arguments’.

This literature is full of crazy words, I’m sorry.

Regarding the name ‘transcendental argument’, Roger Scruton explains that “An argument is transcendental if it ‘transcends’ the limits of empirical enquiry, so as to establish the a priori conditions of experience.”[2]

Sam Pihlström further explains that,

…the medieval notion of transcendentalia [is] still partly at work in the Kantian conception of the generality of transcendental conditions and principles: what the “transcedentals” transcend is not, of course, the boundary of experience (they do not transcend but set it) but the boundaries between all specific ontological and other categories; they concern everything, generally.[3]

So then there is still a relationship between the Medieval’s ‘transcendentals’—which are thought to be explications of the concept of ‘being’ in terms of the “most common notions” such as ‘one’, ‘true’, ‘good’, etc.[4] and which are presupposed by all experience of ‘being’ –and the more modern method of Kantian inspired transcendental argumentation whereby something is shown to exist by being the necessary precondition (or presupposition) of the existence of something else which we take to exist.[5]

Transcendental arguments have typically been employed as anti-skeptical arguments which take a given of human experience, G, and seek to show that something which the skeptic is skeptical about, S, is a necessary precondition of G, such that if we have G then we must have S and since we do in fact have G, therefore we also have S.[6] While the name ‘transcendental arguments’ owes much to Kant and those who’ve came after him, the argumentation style has been put to use in various different ways against skeptics from at least as far back as Aristotle’s indirect argument for the law of non-contradiction,[7] to Augustine’s si fallor sum argument against the skeptical Academicians of his time[8] to Descartes’s appropriation of the same argument in the form of his cogito ergo sum,[9] to modern day attempts at refuting external world skepticism and skepticism about other minds (Donald Davidson[10]), refuting brain-in-a-vat skeptical threats (Hilary Putnam[11]), to refuting naturalistic determinism (William Hasker[12]), and seeking to refutate of naturalistic cognition (Robert Koons[13]).

Okay, so that’s a lot. I know. And we still haven’t gotten to Chesterton! So let’s move this along and define a transcendental argument (TA), as follows:

Transcendental Argument = df. an argument that proceeds from a given aspect of human experience, X, to a necessary precondition (or presupposition) Y, which makes X possible (or intelligible).

“Alright, Park, you’ve gone on enough about transcendentals, now make with the Chesterton!”

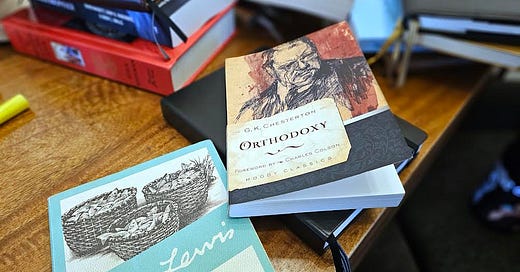

So, in chapter 2 of G.K. Chesterton’s fantastic book, Orthodoxy, he defends what he calls “mysticism” from the “morbid logician” who in this case in a naturalistic materialist, someone who thinks that all we are is matter in motion—no immaterial souls, no God or gods, just the physical realm exists and only that which can be rigorously explained by logic chopping or reduced to physics.

Chesterton presses the free will aspect of the argument from reason against the materialist, claiming that materialism often leads to complete fatalism, or physical causal determinism. This is not my favorite argument from reason, since many physicalists today don’t employ causal determinism in their world-and-life-view, but for those who do, I think this argument is pretty devastating, and not because of libertarian free will, but because physical causal determinism precludes *any* rational deliberation, libertarian or otherwise. I’ll discuss all of this in more detail and with more comprehendible language in the official essays for our C.S. Lewis read a long, but this one’s a kind of bonus so I’m not spending as much time in explanation, sorry!

Chesterton goes on to say,

It is absurd to say that you are especially advancing freedom when you only use free thought to destroy free will. The determinists come to bind, not loose. They may well call their law the “chain” of causation. It is the worst chain that ever fettered a human being.[14]

What a great turn of phrase. The guy was brilliant. So he’s advancing an argument against materialism and especially a materialism which also holds to physical causal determinism, the view that the universe is causally closed, the only forces that act are those described by the laws of physics, and those laws are determinist, there is a causal chain of events that necessitate the next link in the chain. If this is the case, then freedom and rational deliberation, i.e., thinking about and argument and determining what you believe about it according to reason or rational faculties etc., go out the window. But Chesterton goes on to commend his own world-and-life-view, the mystic view, a name which he takes on from his detractors and just runs with—which is yet another hilarious and commendable action by Chesterton:

“G.K., your view of the world amounts to silly, antiquated mysticism, and nothing more.”

“Ah, yes, so anyways, my mysticism is far preferable to your morbid logic chopping and here’s why”.

He goes on to contend with the materialistic determinist and comment his mysticism by claiming that,

The whole secret of mysticism is this: that man can understand everything by the help of what he does not understand. The morbid logician seeks to make everything lucid, and succeeds in making everything mysterious. The mystic allows one thing to be mysterious, and everything else becomes lucid. The determinist makes the theory of causation quite clear, and then finds that he cannot say “if you please” to the housemaid. The Christian permits free will to remain a sacred mystery; but because of this his relations with the housemaid become of a sparkling and crystal clearness. He puts the see of dogma in a central darkness; but it branches forth in all directions with abounding natural health.[15]

So, Chesterton is taking a negative transcendental approach to rebuffing the naturalistic materialist and a positive transcendental approach vindicating his Christian world-and-life-view. He acknowledges that there is mystery in Christian dogma, or doctrine, but if we acknowledge mystery at the start, or at the top, we can make sense of the rest of the world. Whereas if we start from the ground up, we may be able to explain the initial phenomena, like physical causation, but we’ll make our own reasoning and volition an utter mystery. We cannot deny our own volition volitionally… we cannot rationally deliberate that all rational deliberation is illusory, so, any view which would commit us to such a contradiction is transcendentally rebuffed. What must be the case if we are to make sense of our rational capacities and volition? Well, if we are to make such faculties comprehendible, we need to put an incomprehensible God at the center of our world-and-life view.

Chesterton was a master at giving analogies, and here he follows St. Augustine’s notion of divine illumination by giving a sun analogy to bolster his point:

Symbols alone are of even a cloudy value in speaking of this deep matter; and another symbol from physical nature will express sufficiently well the real place of mysticism before mankind. The one created thing which we cannot look at is the one thing in the light of which we look at everything. Like the sun at noonday, mysticism explains everything else by the blaze of its own victorious invisibility… of necessary dogmas and a special creed I shall speak later. But that transcendentalism by which all men live has primarily much the position of the sun in the sky. We are conscious of it as of a kind of splendid confusion; it is something both shining and shapeless, at once a blaze and a blur.[16]

Now those familiar with CSL will recognize the direct influence of the Chesterton quote above on one of CSL’s most oft quoted passages:

Christian theology can fit in science, art, morality, and the sub-Christian religions. The scientific point of view cannot fit in any of these things, not even science itself. I believe in Christianity as I believe that the Sun has risen, not only because I see it, but because by it I see everything else.[17]

Elsewhere, Lewis, following Chesterton, directly connects the ‘transcendental’ and ‘mystical’ language, while arguing against a kind of informal fallacy, which Lewis calls “Bulversim”. Bulverism is a word Lewis invented to pick out fallacy which instead of dealing with the contents of an argument, writes it off based on the psychology of the arguer, e.g., “you just believe that because you’re a woman”. Lewis says,

The forces discrediting reason, themselves depend on reasoning. You must reason even to Bulverize. You are trying to prove that all proofs are invalid. If you fail, you fail. If you succeed, then you fail even more - for the proof that all proofs are invalid must be invalid itself.

The alternative then is either sheer self-contradicting idiocy or else some tenacious belief in our power of reasoning, held in the teeth of all the evidence that Bulverists can bring for a ‘taint’ in this or that human reasoner. I am ready to admit, if you like, that this tenacious belief has something transcendental or mystical about it. What then? Would you rather be a lunatic or a mystic?” (Compelling Reason, pg. 20).

Now CSL is a bit less triumphalist than someone like Cornelius Van Til who argues that a transcendental argument for God’s existence is a knockdown, sure proof. Lewis, following Chesterton and Balfour, focused more on the transcendental nature of Reason, and then went on to argue that Reason is best explained by a Christian world-and-life-view, even while using some language that’s pretty similar to what you’d find in Van Til:

The Validity of rational thought, accepted in an utterly non-naturalistic, transcendental (if you will), supernatural sense, is the necessary presupposition of all other theorizing. There is simply no sense in beginning with a view of the universe and trying to fit the claims of thought in at a later stage. By thinking at all we have claimed that our thoughts are more than mere natural events. All other propositions must be fitted in as best they can round that primary claim. (Compelling Reason. pg. 94).

Alright, so there’s that. This post kind of got away from me to be honest. I love sharing these kinds of quotes with you. I think transcendental arguments are pretty hard to explicate and defend but I love the way Chesterton and CSL use intuitive analogies to get at the heart of the transcendental nature of God and the explanatory power of Christian theism. I’m biting my tongue here because I think Lewis’s best transcendental analogy is in chapter four of Miracles but I can’t jump the gun. Join my read along so you don’t miss it! I promise to make my Miracles companion essays more intelligible to philosophers and non-philosophers alike!

[1] See the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy entry on Medieval Theories of Transcendentals for more: https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/transcendentals-medieval/

[2] Roger Scruton, Kant: A Very Short Introduction (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001) 33.

[3] Sami Pihlström, “Transcendental Anti-Theodicy” in Transcendental Arguments in Moral Theory, eds. Jens peter Brune, Robert Stern, Micha H. Werner (Berlin: Walter de Gruyter GmbH, 2017), 316.

[4] Goris, Wouter and Jan Aertsen, "Medieval Theories of Transcendentals", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2019 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), URL = <https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2019/entries/transcendentals-medieval/>.

Pihlström includes ethics in the transcendentals, “…ethics is transcendental: it concerns everything in the human world, just like the Kantian categories, for example, cover phenomena generally, all objects and events of possible experience.” Though, the medievals would probably subsume ethics under the transcendental ‘goodness’. Sami Pihlström, “Transcendental Anti-Theodicy” in Transcendental Arguments in Moral Theory, eds. Jens peter Brune, Robert Stern, Micha H. Werner (Berlin: Walter de Gruyter GmbH, 2017), 316 n14.

[5] Though Ralph Walker explains that Kant never uses the term ‘transcendental argument” in his writings, instead opting for ‘transcendental deduction’. Walker contends that the form is there even if the language is not, however. Cf. Ralph C.S. Walker, “Kant and Transcendental Arguments” in The Cambridge Companion to Kant and Modern Philosophy ed. Paul Guyer (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011), 238-268.

[6] Cf. Transcendental Arguments in Moral Theory, eds. Jens peter Brune, Robert Stern, Micha H. Werner (Berlin: Walter de Gruyter GmbH, 2017), 1.

[7] “Aristotle’s “elenctic refutation” has been fruitfully compared to a Kantian transcendental argument. Transcendental arguments generally run as follows: If certain aspects of experience or thinking are possible, the world must be a certain way. Since these aspects of experience or thinking do exist, the world is a certain way. These aspects of our experience or thinking presuppose that the world is a certain way. That the world is a certain way explains these aspects of our experience or thinking and not the other way round. On this interpretation, Aristotle would be arguing that the world conforms to PNC, or that PNC is true, because it is presupposed by and explains the opponent’s ability to say something significant.” Gottlieb, Paula, “Aristotle on Non-contradiction”, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2019 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), URL = <https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2019/entries/aristotle-noncontradiction/>

[8] Augustine, Against the Academicians and The Teacher, (Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Company, 1995) 163.

[9] Cf. the Internet Encyclopedia entry on transcendental arguments under section 4 on “the verificationism/idealism objection”: https://iep.utm.edu/trans-ar/

[10] See Robert H. Myers and Claudine Verheggen, Donald Davidson’s Triangulation Argument: A Philosophical Inquiry (New York: Routledge, 2016)

[11] Hilary Putnam, “Brains in a vat” in Reason, Truth, and History (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1981), 7.

[12] William Hasker, “The Transcendental Refutation of Determinism” in Southern Journal of Philosophy, Fall 1973, 175-183.

[13] Robert C. Koons, “The General Argument from Intuition” in Two Dozen (Or So) Arguments for God ed. Jerry L. Wallys and Trent Dougherty (NY: Oxford University Press, 2018), 245.

[14] G.K. Chesterton, Orthodoxy (Chicago: Moody Classics, 2009), 42.

[15] G.K. Chesterton, Orthodoxy (Chicago: Moody Classics, 2009), 47.

[16] G.K. Chesterton, Orthodoxy (Chicago: Moody Classics, 2009), 48.

[17] C.S. Lewis, “Is Theology Poetry?” in The Weight of Glory (HarperOne, 1980), 140.

Isn’t it the 100th Anniversary of THE EVERLASTING MAN? What a book that is. Could be a great book club style book.

I’ve read this post 7–8 times over the past few days, and I still feel like a lot of it went over my head. But I’m sure you’re the best person to break it down for folks like us—interested in philosophy, without a formal background. Please don’t worry about the length if you need to digress a bit to explain things. It’s useful and makes sense when you do, we’ll stick with it till the end. Thank-you for writing!😊