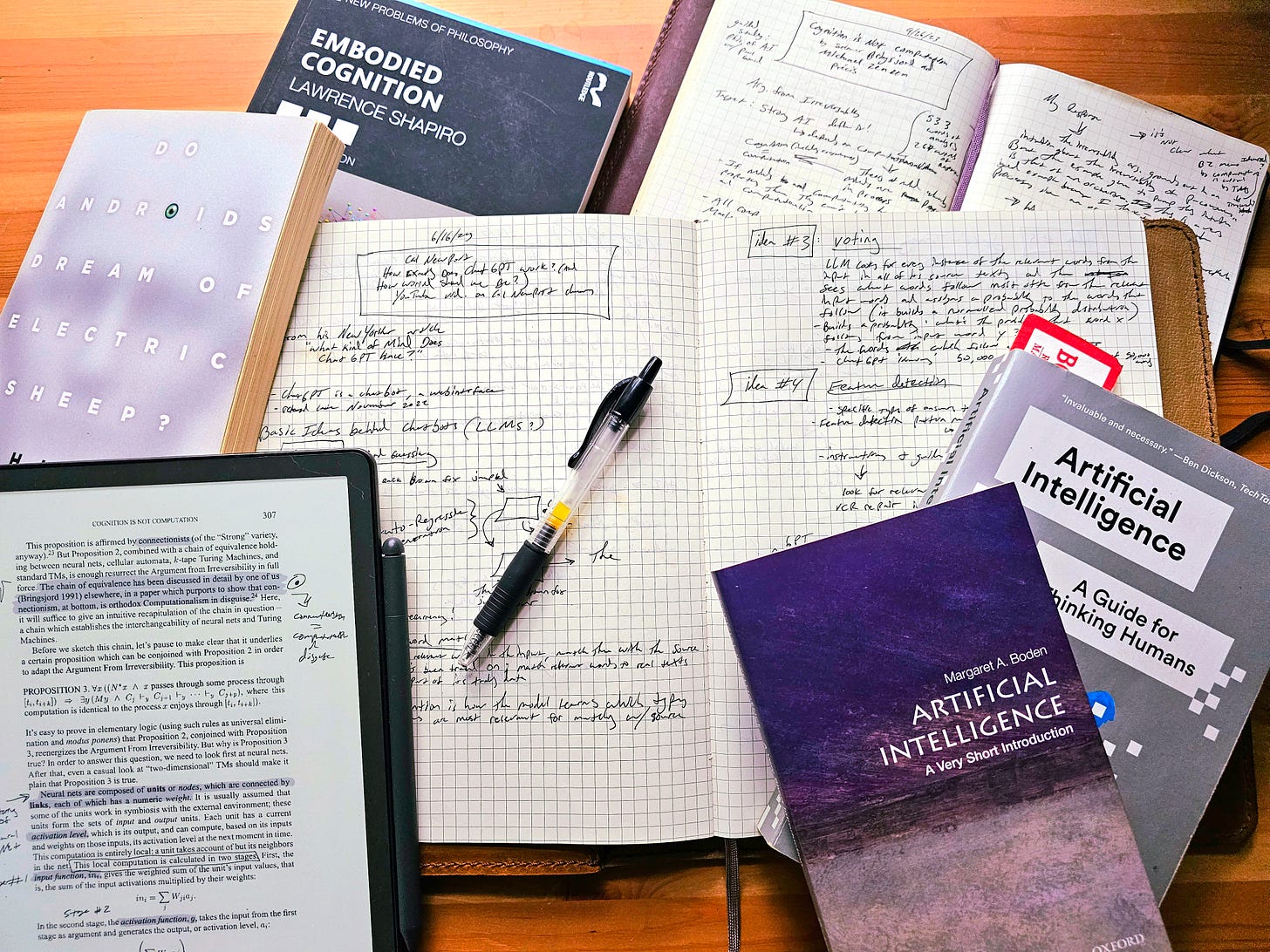

How to Create Your Own University Course to Teach Yourself Almost Anything

Give Structure to Your Autodidact Studies and You'll Learn Way More

You can teach yourself an absolute ton of stuff today. There are so many free resources out there just waiting—begging!—to be utilized, from YouTube lecture videos to Substack articles to the occasional gold mine of an info-dump-reddit-post. There is a lot of info available today for the motivated autodidact.

But motivation isn’t enough. If your self-study is built on raw motivation alone, you’re in for a bad time. Motivation often waxes and wanes without our consent, and you can find yourself on the other side of a long waning period kicking yourself for letting so much time elapse in your self-study.

So don’t do it like that. Motivation is great, but if you give yourself some structure, you might be able to stoke your motivation and learn even more than you ever expected.

I suggest that you structure your self-study in a sort of university-style course and give yourself seasons to dive deep into the subjects you want to learn or master.

Seasonality means you’re not stuck in this subject for eternity so you shouldn’t feel trapped but the clock is ticking so you also don’t want to squander the time you’ve allotted for this subject. Say what you will about the universities, discrete courses set on a schedule are a pretty great idea.

If you like this post, you can grab it in a digital download or physical copy in issue 1 of my new zine, Proverb Peddling: Philosophy for Wisdom Lovers

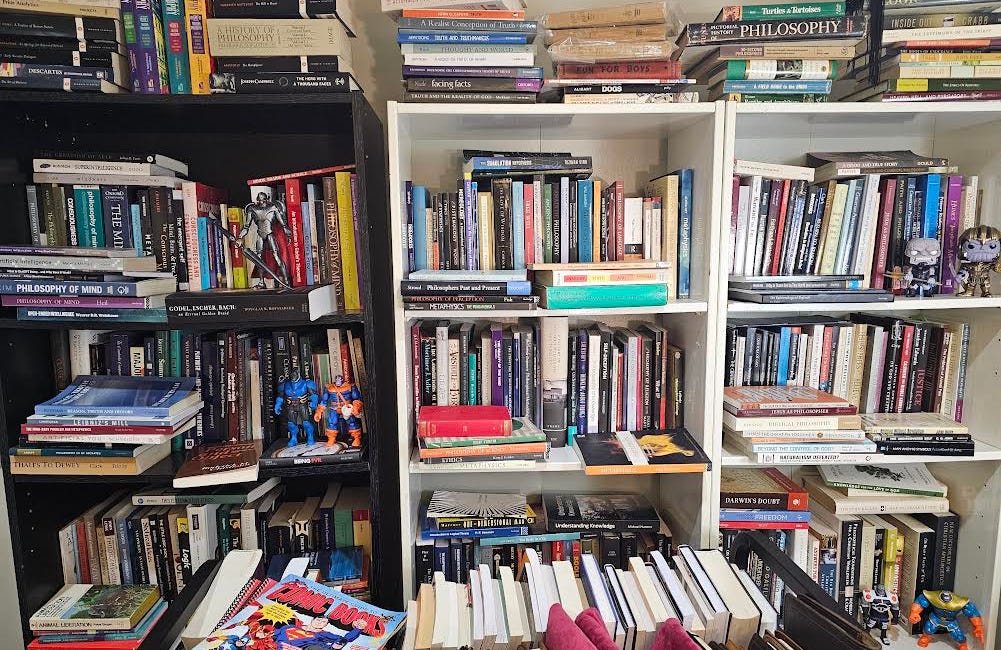

In my last year of undergrad I realized I actually love to learn, I was just studying the wrong stuff: kinesiology. Being jacked sounds great but it was philosophy and theology that truly sparked my interest and stoked my soul. After graduation, I began my own self-study of philosophy and theology for 5 years before entering grad school where I earned 3 Master’s degrees in 11 semesters, completing ~115 credit hours. It was a wild ride for sure (I had tuition wavers and scholarships which caused me to pig out on lots of extra classes I wouldn’t have taken if I had to pay for them).

There were some semesters where I was taking 19 credit hours including courses in Koine Greek and ancient Hebrew. That course load probably would have killed me if I hadn’t been preparing myself with self-learning university style-courses for the 5 years prior to my graduate work.

So, making your own autodidact courses can help you learn and master new topics and they can help prepare you for formal study if you choose to go that route later on.

Hopefully I’ve piqued your interest by now because I want to jump in on the details. Here’s how you can go about making your own self-study course to teach yourself more than you thought possible.

How to Make Your Own University-Style Courses

1. Pick the Topic of Your University-Style Course

First off you need to pick the topic of your course. Seems pretty self-explanatory but you should sit down and give some serious thought to what you’d like to study. Do you want an introduction to biology? Would you like to take a deep dive into herpetology? Maybe ancient philosophy? Contemporary theology? Maybe the history of automation or of artificial intelligence or of the bicycle? What about the history of beer, or Mongolian folklore, or art history or the Japanese mythology behind the Pokémon universe, or a political science primer? Maybe a deep dive into the principles of economics?

The potential is overwhelming. You could study anything! But you can’t study everything. So narrow it down and the more time you spend giving serious thought to the topic of your self-study course, the more secure you’ll be in your decision and the less you’ll thrash against your schedule when it comes time to actually sit down and study.

So what are you going to study?

Reminder: you can support my mission to promote the life of the mind AND you can get tons of members-only content for a few dollars a month. Content like:

full-length notebook philosophy essays/tutorials where I share in-depth instructions on how to use various notebook methods and the philosophers who inspired each method

members-only access to For the Love of Wisdom entries (my digital intro to philosophy text book)

members-only access to Sayings of the Sages, my digital commonplace book of wise sayings I’ve collected over my years of studying philosophy and culture

access to our Zoom Book Club sessions where we discuss the read-along books and my companion essays

the full catalog of members-only essays + lecture videos

access to the members only chat

and lots more!

2. Determine the Number of ‘Credit Hours’

You have your topic, now how much time are you going to allot to studying it? Can you give yourself 2 hours a week for self-studying lecture videos you’ve found or podcast episodes on the topic you’ve selected? If so, then you’ve got yourself a 2 credit hour class.

Now who’s crediting you for those hours? You are! At the end of your course you can add up all the sessions and time spent watching lectures and give yourself a final tally.

Maybe you set the duration of the course for 6 weeks and watched 2 hours of material per week. That’s 12 hours you spent on your topic! And that’s not counting the time spent reading your course material or writing your reflection papers, precís, book reviews, or research papers—we’ll get to those below.

So determine how much time you can actually afford to dedicate to listening to lectures/podcasts per week and write that down as your number of credit hours. Can you only do 1 hour? That’s okay, do what you can. Can you devote 5 or 6? That’s great, write it down.

You may be confident that you can listen to lectures or podcasts during your commute and still retain the information you learn from them. If that’s true, then you’ll have an advantage but if that’s not true of you then set your goals lower so you don’t get overwhelmed. That way any amount of study time spent above and beyond the hours you’ve allotted are bonus. It feels much better to get bonus time than to fall short of your written goals.

Next, determine how long your self-study course will run. I think 6 weeks is a pretty good amount of time if you’re learning something new. It shouldn’t be too overwhelming—the end is always in sight. But it’s long enough for you to actually become acquainted with most material. So maybe start with a 6 week course and if it’s too short just consider it 101 and make another course called 102 and run it back for another 6 weeks. Maybe you discover you love this method and you want to extend your courses to a full semester or to a season of the year—you can surely do that, it’s your course! Maybe you want to challenge yourself with a quick deep dive and after you tried a 6 week course you want to do a speed run ultra learning course with some vacation time or something—you can definitely do that as well.

But don’t make a super short or super long course, burn out, and then come and blame me! Start nice and easy and then get crazy after you’ve seen some success.

So determine the weekly credit hours (for consuming lecture/podcast material) and determine how long your course will run. I suggest 3 to 5 credit hours per week for 6 weeks.

3. Create a Course Description & Syllabus

You have the topic, you’ve determined how much time you can devote to listening to experts teach on your subject per week, and you know how long your course is going to run. Now you need to come up with a course description.

Give your course a name, for example “Intro to the Philosophy of J.R.R. Tolkien” or “Intro to Cognitive Science”. You may even give your “University” it’s own name if you plan on continuing on with your own university-style courses. This can get really cheesy, real fast, so be careful lest you make a cool thing into a very lame thing.

But once you have your course title, then you will literally write up a course description and syllabus in a Microsoft Word document or some other analog—could be in your self-study notebook(!).

What is your course about?

What are the desired outcomes? What do you hope to learn? At the end of this course, what should you know and be able to talk about?

What Assignments will you complete?

Something simple like the following could suffice for a course description:

“In this course I will study the history of Western philosophy from Thales to Descartes. I will explore the philosophical ideas of the prominent philosophers from the time of the presocratics up through the modern rationalists like Descartes. I hope to gain a better grasp on Western philosophy and become more conversant with the great ideas put forth by Western philosophers.”

Just describe the course you’re making and write down what you expect to get out of it.

As for assignments, I think you should write some papers. I’m sorry, but I think it will be good for you. 1 bigger research paper, where you pick a topic and do a deeper dive into it and then write about it. Maybe comparing and contrasting rival schools of thought (philosophical schools or ideas, economic schools, biological categorization schools of thought, whatever), or diving deep into one single thing you’d really like to learn about, maybe the classification of the 3 subspecies of alligator snapping turtles and why those categories continue to change. You’ll have to fill in the details for your own research paper but I think you should write one to make yourself catalyze what you’ve learned from you course.

No one else ever has to see your research paper—but you might consider posting it somewhere for feedback—not reddit probably unless you have a thick skin, they’re brutal. But you can find a Facebook group or a discord channel or if you have a friend in the field, maybe email it to them for some feedback. You might even post it on your own Substack publication. If you know other eyes are going to be on it, it can help you take the project more seriously which will in turn help you study more rigorously. But if that stresses you out too much, then just write it for yourself. It will be helpful to go back and read when you want a refresher on the topic. I reread my old research papers all the time and they’re a huge help.

Secondly, I think you should write a book review or a precís on one of your assigned readings. Yes, I think you should assign yourself readings along with the lecture material which you’ll watch to fulfill your weekly credit hours.

Just write up a 1 page precís on at least one of the things you read. A precís is basically an analytic summary. Here’s what the author argued for and here’s what they used to support their argument. Judgement free. Just the facts.

A review is a little more in-depth. You’ll give a summary and then give your own judgement on the piece you read. Was it well written? Did they support their thesis adequately? What were some key take-aways for you? Would you read it again? Why or why not? And you can keep this around 2 or 3 pages. Again, you might consider publishing this for feedback from others, maybe on Goodreads or Substack, Facebook, or some other platform. But if it’s just for you, that’s okay too, just do the work. It will enhance your reading experience if you know you’re going to have to write about what you’re reading. You will pay closer attention and learn more.

So write 1 research paper and 1 review or precís.

4. Find Your Course Material

Here’s one of the hardest parts: finding your course material. Maybe you can find a professor who has uploaded their course lectures to YouTube. There are actually a ton who do this now and bless them for it! I’m mostly in the philosophy world and I know there is really great content from folks like Gregory B. Sadler. The late Arthur Holmes has a History of Philosophy lecture series comprised of 81 lectures on YouTube!! I listened to it during own of my own self-study courses back in 2014 and it was amazing. You can also find podcasts like Philosophize This! and the History of Philosophy Without Any Gaps, or even my own podcast, Parker’s Pensées—I have lots of different playlists on topics like the philosophy of AI, Stoicism, the philosophy of mind, and more.

So if you want to study philosophy you have lots of options! For other topics you may have to get more creative but if you know how long your course is and how many hours per week you’re going to be listening to ‘lectures’, then you can do some preliminary research and find the exact number of videos you’ll need to watch during your course. Then you can find the specific videos that you’re going to watch, and make a YouTube playlist with all the videos you are going to listen to for your course. You can do the same thing with a Spotify playlist as well—or whatever other analog of your choosing. Title the playlist/s with the same name you gave your course and boom, you have your lecture material all in one spot!

Books and papers and other required readings will be harder to find but you should be able to outsource some of the reading list to others who know more than you. Take to YouTube comments, Facebook groups, subreddits, Twitter, Substack, or some other platform and ask people for the top 5 or 6 books they’d recommend you read in your self-study of your topic. Even if people are jerks, they still love showing off what they know and what they’ve read. If 4 or 5 books continue to pop up on various recommended lists, then those are probably books you should add to your required reading.

Additionally, you might troll through Substack and bookmark a bunch of pieces from experts on the topic you’re going to be studying. This is a great way to finally get caught up on your favorite substackers as well.

Now 6 weeks is a pretty quick course. You probably can’t read 4 books in that time, but you might be able to read 2 books or 1 book and several articles. You’ll have to be honest with yourself and determine how much you can read in that time period (or how much you can listen to on audio book if you’re going that route).

This course is just your first stab at learning the topic so don’t stress out and try to read everything. If you end up loving the topic, make a follow up course and extend the time frame then read and watch a bunch more.

5. Schedule Your Course Times - Course Outline & Agenda

Okay, you found your lectures and required readings. Now you need to fill in your syllabus with the course outline and agenda—when are you going to watch/listen to the lecture material? When are you going to do your required readings?

If you don’t schedule a time, you’ll never get through the course material. So take your course seriously and block out times in your calendar to listen to your lectures, just like you would do if you were in an actual university course. Maybe it’s Monday, Wednesday, and Friday mornings for an hour each. Sit down and plan out where each of the lectures you’ve found will go and then put it in your calendar before you start your course. This way all of your lectures are mapped out and all you have to do is follow your agenda.

Likewise, you’ll need to plan times to do your readings. Block out an hour a day to do your uninterrupted readings. You could also plan to read on the off days when you’re not watching/listening to your lecture material. In grad school, I had a ton of reading to do so I had to plan out the exact pages of each book/article from my required reading so I knew I was staying on track in each class. You might enjoy this as well. “I know I have to read 35 pages of the Fellowship of the Ring on Tuesday, Wednesday, and Friday next week to stay current with my course schedule”.

Whatever method you end up choosing, fill in the details of your course agenda so you know what you need to do every day during your course. The more initial planning you do, the less ad hoc planning you’ll need to do during the course and the more you can focus on learning the material you want to learn.

If you’re learning something useful from this post and want to say thanks, now you can buy me a coffee:

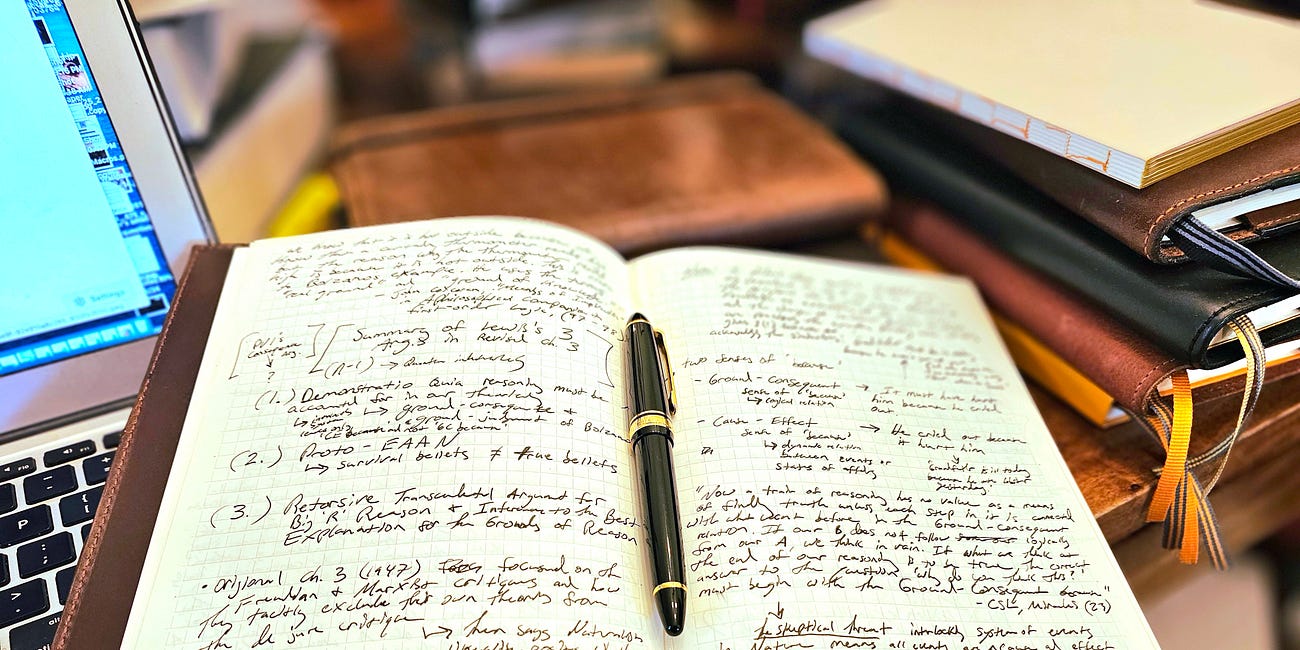

6. Take Notes!

Note-taking is huge. I understand if you have to listen to your lectures during your commute, but if that commute is by train or some other mode where you can be taking notes while listening, then you really should take notes! If you have to be driving while listening, then leave earlier and give yourself 10 minutes before work to take notes on what you just listened to during your drive. A quick active-recall summary session after your lecture material will go a very long way!

Mark up your books and articles if you can. Marginal notes are just the best. I will write more on this here on Paker’s Ponderings but here are a few pieces I wrote on how to remember what you’ve read, including tips on marginal notes and notebooks dedicated to book notes:

Remember What You Read | 5 Ways to Keep a Notebook of Book Notes

This post is too long for email. Sorry about that. It’s jammed too full of good tips, resources, and pictures of my own marginal notes and notebooks. So, just follow the prompts to the website in order to read the full post with all of the reading tips. Now on to the post:

How to Keep a Compendium Notebook

I'm talking about compendia! Make yourself atleast one paper notebook compendium on a given interest. These are the best tools to help you get acquainted with new topics and master those topics you want to be an expert in. I'll explain why, I'll characterize 4 different kinds of compendia you could keep, and then I’ll show you how to start one from scratch.

Here’s the entire subsection of my Substack called Notebook Philosophy on all the different study habits I use to help myself remember what I read and help me get clear on what I think about what I’ve read: Notebook Philosophy subsection

Feedback

Okay, now I want to hear from you all! I know some of you reading this also have helpful tips so drop those in the comments and let’s all grow together!

You can also watch my video version of this piece over on my YT channel, ParkNotes:

I like to add a resource for free learning to your list: university level open courses. Yale, Harvard, Stanford, MIT, etc, have free online courses. Some are short (30 min excerpts from longer courses), some are full lecture series. I'm listening to one now from Yale on Philosophy. I created a Notion form to take study notes. And if I come across relevant conversations online (like this one), I share what I learn. Thank you for your post. It inspires me to keep going...and maybe even to write a paper. 😊

If you’re looking for readings, try contacting your local public library and asking a reference librarian!

They can help with finding books, borrowing books and articles for free from other libraries (inter library loan), and helping you find influential texts and journals in any field.

Plus, library usage is one of the metrics that most municipalities use to decide how much money to give the library year to year. Using the library that your taxes already fund is a great way to help them have money to buy more great resources, among lots of other important services.