"I Will Discipline You With Scorpions!"

The Sons of Philosopher-Kings Aren't Okay...

States will never be happy until rulers become philosophers or philosophers become rulers… but even then their sons will take power and completely wreck the very state itself…

Wisdom is not inheritable. If it were, perhaps we’d have more wise kings and emperors, but it’s definitely not and we have two prime examples: Commodus and Rehoboam.

Commodus was the son of Roman Emperor Marcus Aurelius, who some have seen as the ideal instantiation of Plato’s ‘philosopher-king’. In the introduction to the Modern Library edition of Meditations, Gregory Hays notes that Marcus Aurelius was “fond of quoting Plato’s dictum” about philosophers becoming rulers or rules becoming philosophers for the state to flourish. He claims that while Marcus himself would have chafed at the title ‘philosopher-ruler’ or ‘philosopher-king’ being applied to himself since he didn’t consider himself a philosopher, nonetheless,

those who have written about him have rarely been able to resist applying it to Marcus himself. And indeed, if we seek Plato’s philosopher-king in the flesh we could hardly d better than Marcus, the ruler of the Roman Empire for almost two decades and author of the immortal Meditations.[1]

Now I’ll admit, Marcus does seem like a good candidate for the title of philosopher-king, but perhaps an even better candidate is King Solomon of Israel. King Solomon was the third king of Israel after his father, King David, and his predecessor, King Saul. Solomon is seen as the wisest man in the Bible, prior to Christ. He asked God for wisdom to rule the nation well instead of asking for wealth or power and God delivered. Solomon spent his time solving difficult legal cases, counseling foreign kings and queens, writing treatises on animals, creating lush forests and lakes, and collating wise sayings and even generating his own proverbs. Solomon certainly fits the description of a philosopher-king, but he did so ~500 years prior to Plato coining the term (though Plato actually called them something like “philosopher guardians” but philosopher-king is much more epic).

So, we have Emperor Marcus Aurelius, the pagan philosopher-king, who wrote his own rich work of philosophy called Meditations, which millions have found comfort and guidance in, but which was meant solely as a personal journal. And we have King Solomon, the biblical philosopher-king, who crafted a commonplace book of wisdom, constituted by a collection of both the sayings of the wise, as well as his own wise sayings, which was dedicated to his sons to guide them in living well—read by billions.

So how did the sons of Marcus and Solomon fair, given that they were raised by two of the wisest philosopher-kings in human history?

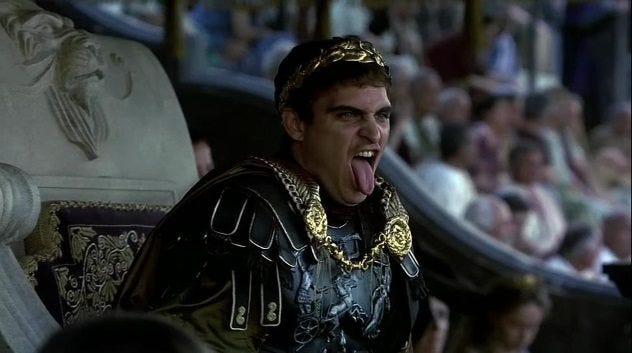

Well, Marcus named his son, Lucius, co-emperor with himself in 177 AD. Marcus died in 180 AD, Lucius then became the sole emperor of Rome and changed his name to Marcus Aurelius Commodus Antonius. But Commodus quickly lapsed into insanity,

He gave Rome a new name, Colonia Commodiana (Colony of Commodus), and imagined that he was the god Hercules, entering the arena to fight as a gladiator or to kill lions with bow and arrow. On December 31, 192, his advisers had him strangled by a champion wrestler, following his announcement the day before that he would assume the consulship, dressed as a gladiator. A grateful Senate proclaimed a new emperor—the city prefect, Publius Helvius Pertinax—but the empire quickly slipped into civil war.[2]

So, that’s not great. What about Solomon’s successor son?

Rehoboam took over as king for Solomon when he passed away. His people said, “hey, your father’s rule was hard, he made our yoke heavy. Lighten our load and we will love and serve you well.” So, Rehoboam asked for some time to consider this. He took three days and asked for counsel from his father’s wise men. They all counseled him to be kind to the people, to be a servant king, so that the people of Israel will love him and be loyal to him forever. Instead, he took counsel from his young friends who told him to say, “My little finger is thicker than my father’s thighs”, which is actually a crass innuendo at his father’s expense. Rehoboam was wise enough not to repeat the innuendo, but he did say the rest of what they suggested: “My father made your yoke heavy, but I will add to your yoke. My father disciplined you with whips, but I will discipline you with scorpions.”[3]

Naturally, the people didn’t like the prospect of being whipped with scorpions, so the people of the north seceded and made for themselves a new king. The nation or Israel was split into the northern kingdom, still called Israel, and the southern kingdom, called Judah.

So, what the heck? Two of the wisest philosopher leaders in history left their kingdoms to absolutely psychopathic sons who completely wrecked their legacies within a single generation, leading to civil wars and continued strife for both people groups. What’s the lesson here? Were they too busy studying philosophy and dealing with statecraft to raise their sons well? Were they too blinded by their own genealogies to find more suitable successors? I don’t know. It’s odd, right?

It’s not just that their sons were average dullards, it’s that they were such spectacular fools and failures. The contrast between fathers and sons is really striking. It’s tragic and comical. I don’t really have a lesson for us here, just wanted to note these twin phenomena I came across as I’ve been studying philosopher-kings for my science fiction novel.

If I had to come up with a moral of the two stories, it might go like this: maybe don’t give the reigns to your son if he’s a foolish pyscho and maybe don’t be so wrapped up in being wise or being excellent at your craft that you forget to father your boys into their own wisdom and virtue.

[1] Gregory Hays, Introduction to Meditations by Marcus Aurelius (NY: Modern Library, 2002), vii.

[2] https://www.britannica.com/biography/Commodus

[3] 1 Kings 12:14

this is very insightful. It led me to some better understandings myself. Keep up the good works!

Never stop writing ♥️