The Very Best Tool for Intellectual Growth

A Brief(ish) History & Analysis of Commonplace Books

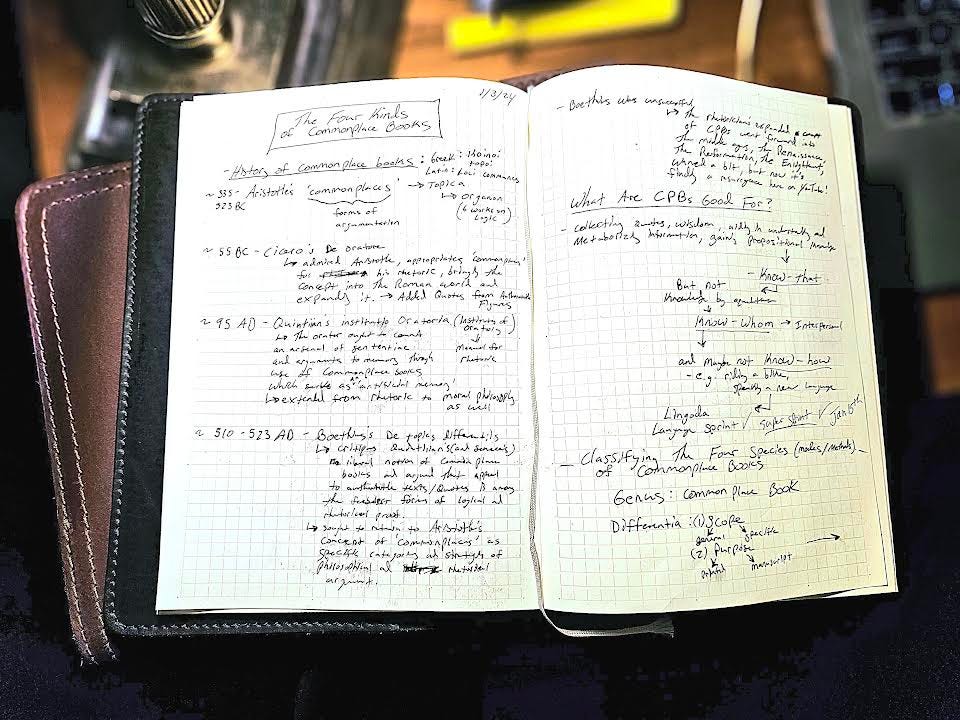

Commonplace books are the best way to master your favorite topics or learn new subjects. Many of us stumbled into reinventing commonplace books (CPBs) in our own personal study only to later find out that this is a common practice amongst some of the finest scholars in human history, stretching back through the renaissance, through ancient Roman philosophers, and all the way back at least as far BC as King Solomon.

This post is long and probably boring. If you want to watch my videos on CPBs—they’re way more exciting—then feel free… no feel constrained to watch this playlist of all the videos I’ve made specifically on CPBs:

ParkNotes Commonplace Book playlist

If you want to find the resources where I found out all this information on CPBs or If you want to grab some materials to start or continue commonplace booking, then check out my Amazon Storefront Commonplace Book Idea List. Buying books or stationary from my store helps support my work and justifies me writing this long post. Check it out here: Parker's Amazon Storefront

Here’s some more affiliate links before we get started, check them out for discounts and to support my work:

Field Notes: 10% off entire order with promo code PARKERNOTES at checkout: Field Notes Affiliate Link

Murdy Creative Co: 10% your entire order with promo code PARKERNOTES at checkout: Murdy Creative Co affiliate link

Saddleback Leather Co: no discount but if you’re going to grab something, like this awesome leather notebook cover, then use my link to support my work: Saddleback Leather Affiliate Link

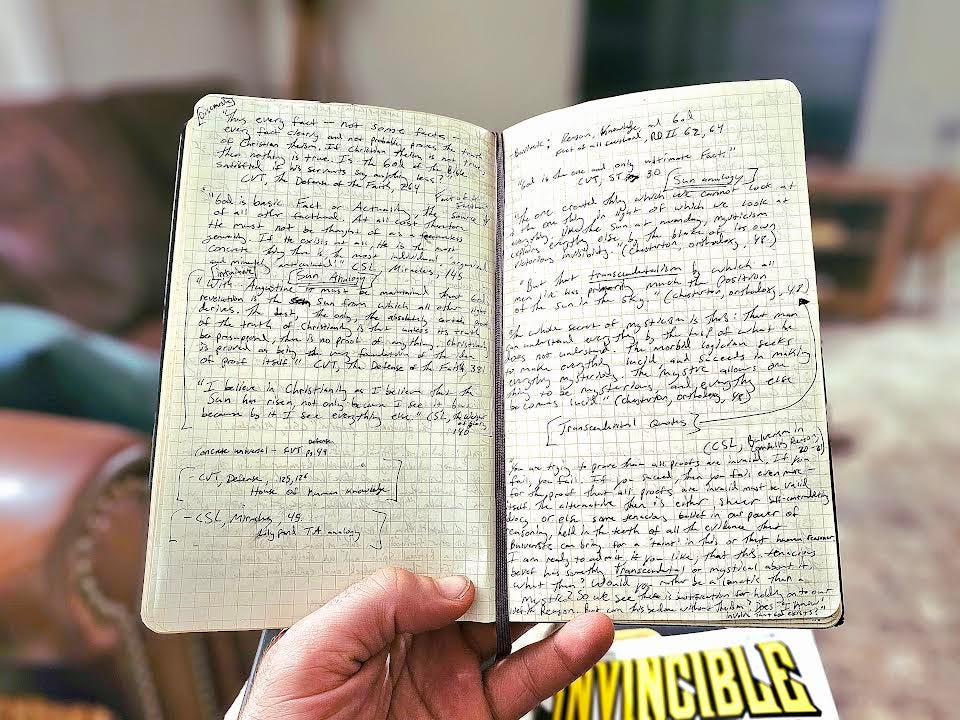

I started my first commonplace books back in 2013 after God woke me up to a new love for education. I began listening to lots and lots of philosophy lectures, apologetics debates and presentations, sermons, theology lessons, podcasts, and just about anything I could get my ears on. I also started teaching myself (forcing myself) to actually read for comprehension and to complete the books and papers I started reading. Slowly but surely, I began to grow as a reader (and I mean slowly! I used to fall asleep after reading just two pages).

But with all this new information coming in, I needed a way to collate it for future reference. I thought about all the authors and public speakers I was listening to and I marveled at their breadth of knowledge and mastery of gnomic sayings. I figured the best way for me to become a person like them was to create collections of quotes and ruminate back on them in order to make them my own. If I could just keep them in one spot, then I could read them over ad nauseam and never get caught without an aphorism on my lips. So that’s what I started doing.

It wasn’t until five years later when I entered seminary that I discovered