Don't Be a Sophist About Miracles | ch. 7&8 of C.S. Lewis's Miracles

Red Herrings and The Laws of Nature

Welcome to the Parker’s Ponderings read-along of Miracles by C.S. Lewis. This is the fourth companion essay I’ve put out and in it I’ll be covering chapters 7-8 of the book. If you’re just discovering this read-along for the first time, you can catch up by reading the first companion essay, which covers chapters 1&2, here, and then read the second companion essay, which covers chapter 3, here, and chapters 4-6 here.

Here’s the read-along schedule again:

March 31st - Chapters 1-2 – World-and-life views, presuppositions, and the philosophy of fact

April 9th - Chapter 3 – Three Arguments from Reason Against Naturalism

April 11th – Chapters 4-6 – Four or Five More Arguments from Reason

Zoom Call for Paid Subscribers #1 – April 13th from 1:00pm – 2 or 2:30pm central

April 15th – Chapters 7-8 – common objections to miracles, the nature of nature, and what miracles are not

April 21st - Chapters 9-12 – The Author Analogy, The Ultimate Fact, Doctrine of God

Zoom Call for Paid Subscribers #2 – to be determined

April 28th - Chapters 13-14 – Presuppositions and Argument from Reason revisited, Criterion of Miracles, a Theology of Religions

May 5th – Chapters 15-Appendix B – The True Myth, One vs. Two-Floor Realities, Against Monism, Author Analogy Revisited

Zoom Call for Paid Subscribers #3 – to be determined

You Did It!

We’re past the hardest stuff in the book now! Congrats! If you are still with me then you’ve made it farther than many CSL lovers have! Even if you don’t fully grasp his arguments, you read through and you persisted and I’m proud of you. Genuinely, a lot of people have given up on the book because of the first 6 chapters but there is so much more gold to be mined in the rest of the book. So if you haven’t had fun so far, get ready to. I’m also going to be shortening up these companion essays because the arguments are much more straight forward from here on out and won’t need as much commentary or explanation.

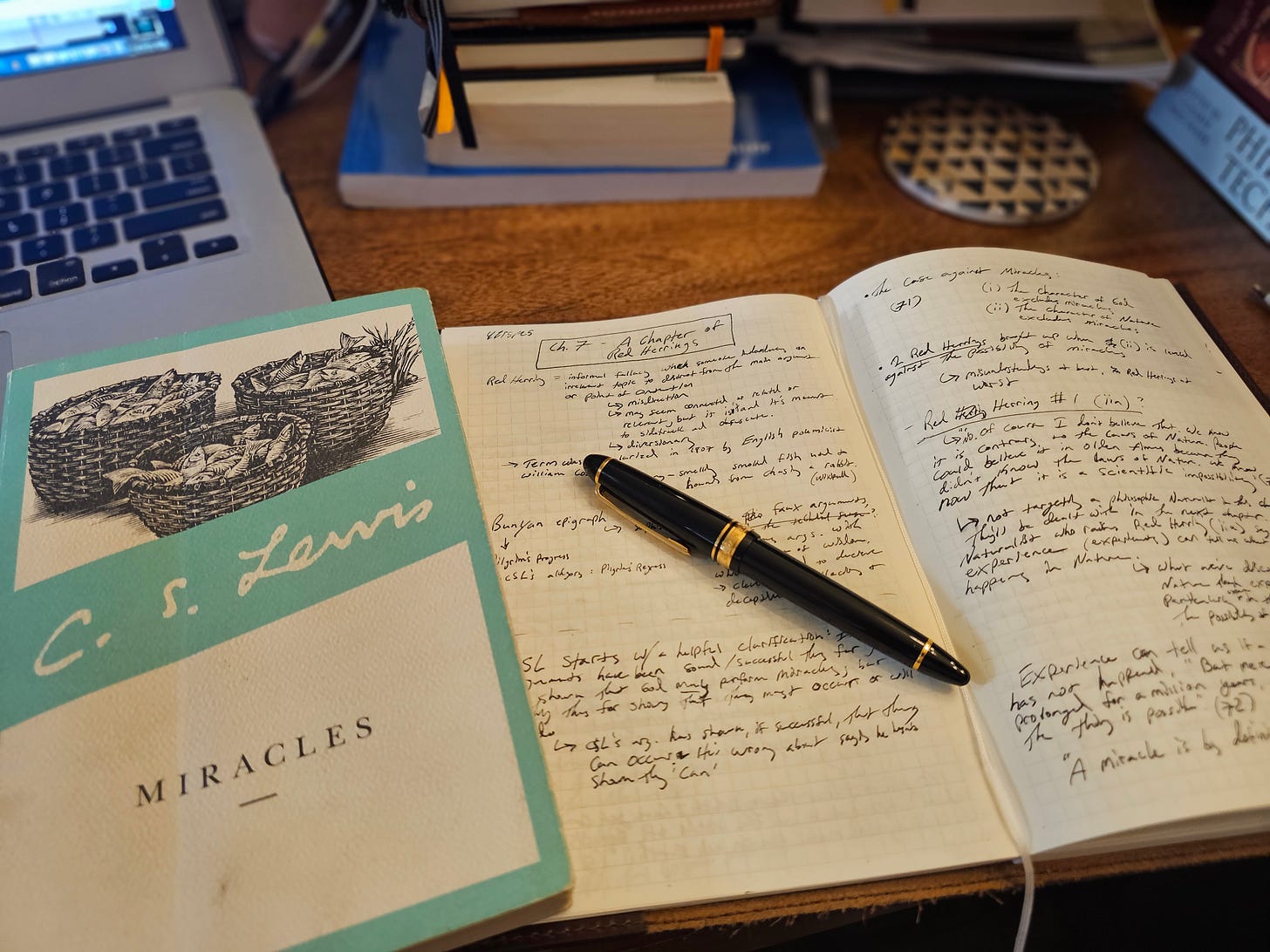

Ch. 7 – A Chapter of Red Herrings

CSL starts us off with a nice little epigraph from John Bunyan’s The Pilgrim’s Progress, which is a famous allegory for the Christian life. Now, it is often said that CSL wrote Narnia as an allegory—but it’s not. Allegories are supposed to have a 1-1 correlation between the things being allegorized, and Narnia just isn’t that kind of thing. But CSL did write an allegorical story right after becoming a Christian and it’s called The ‘Pilgrim’s Regress’ as an intentional nod to Bunyan. So it’s cool to see him referenced here once again in the epigraph to chapter 7.

As a little aside, “sophistry”, from that Bunyan quote, refers to the Sophists, from the Greek word sophia, which means ‘wisdom’ (think philo-sophia, the love of wisdom). The Sophists were pretend sages however. They were less wise men, more philosophical mercenaries (or prostitutes?) and they were the historical rivals to philosophers like Socrates and Plato. The Sophists would take up your case and use their philosophical training to argue your points for you for the right price, despite the truth of the matter. Socrates, on the other hand, was willing to lose his life for what he thought was true, and he did!

‘Sophistry’ is associated with the Sophists and has come to mean something like “clever faux arguments, fallacious reasoning with the appearance of wisdom, which is intended to deceive”. You don’t want to be a Sophist, nor do you want to be accused of sophistry.

Sophists used fallacious arguments like the arguments which CSL calls out in this chapter: red herrings. A red herring is a fish, but it’s also an informal logical fallacy. It’s ‘informal’ because the problem with the argument doesn’t have to do with the ‘form’ of the argument, it may be valid in its formulation, the premises may follow from one another and the conclusion may follow from them, but that alone doesn’t make it a good form of reasoning. A red herring fallacy is when someone introduces an irrelevancy in order to distract from the main argument or point of contention. It’s a misdirection, though it may seem connected or related or relevant but it’s not. It’s classic sidesteppery obfuscation. Exactly what a Sophist would pull.

The ‘red herring’ as fallacy was popularized by an English Polemicist named William Cobbett in 1807 who compared this kind of diversionary tactic to dragging a strong-smelling smoked fish across the scent of a rabbit to divert the hounds. So a Sophist will drag an irrelevant topic across our conversation to divert us from sniffing out the truth.

In chapter 7, CSL raised two such red herrings which are often brought up in conversations on miracles and smacks them out of the way. But before he does that, CSL sets up the potential case against miracles which still might be made even in light of all the time he spent tilling the soil of own minds in preparation for the possibility of miracles in chapters 1-6. He says the case against miracles can be made on one of two points:

(i) The character of God excludes miracles—maybe something about God would keep him from ever performing miracles.

(ii) The character of Nature and its excludes miracles—no miracle could possibly happen do to the intrinsic nature of…well, Nature.

CSL gets into a some philosophy of science type reasoning in chapter 8 as he discusses three views on the laws of nature and their implications for the possibility of miracles, but here in 7 he focuses on two common red herrings:

a. Perhaps in olden times those simpletons could believe in miracles but today we know about the laws of nature and that miracles cannot happen since the are contrary to the laws of nature. (paraphrased from pg. 72)

b. The immensity of the universe debunks miraculous accounts since God would never care about a tiny pale blue dot like us. (paraphrased from pg. 77)

In slapping down (a), Lewis notes that “Belief in miracles, far from depending on an ignorance of the laws of nature, is only possible in so far as those laws are known.” (75). What a profound point, which turns out to be so simple and obvious upon reflection! If you had no concept of induction (the principle that says that nature is uniform and the future will be like the past), and no idea of regularity and laws of nature, you’d never think anything was a miracle, it’d just be another event—if you could even form that concept.

So CSL notes that you won’t be able to perceive and believe a miracle if your philosophy rules out miracles from the start—as he noted in chapter 1—but neither will you be able to recognize a miracle if you don’t have any notion of the laws of nature and regularity. So, while the ancients may not have known as much about the laws of physics and constants, and while they didn’t have equations like E=MC2, they did know that women don’t become spontaneously pregnant, and so Joseph sought to quietly break his engagement to Mary upon learning that she was pregnant. Lewis further notes that Joseph didn’t know as much as a modern OB-GYN but he did know enough to think that his wife had laid with another man and become pregnant. It took the appearance of an angel (another miracle) to convince him of the miracle that took place in his fiancé’s womb.

Lewis acknowledges that various sciences have ruled out various creatures of myth and folklore, and even other false sciences through observations and experiments but those things which have been ruled out were thought to be parts of nature, rather than supernatural interference with nature. It’s a red herring to argue “the ancients were dummies, we know laws of nature, therefore no miracles”.

In slapping down (b), CSL notes that no matter the facts, one could also rule out God and miracles if one’s presuppositions preclude them. He says we treat God like an unjust policeman treats a subject, whatever God does will be used in evidence against him (pg.80).

If the universe is vast and immense then there couldn’t possibly be the kind of God described in the Bible who cares about the needs and personal dealings of tiny old humans on a tiny little blue speck. But if the universe is small and mostly empty, well then that too could be used against the existence of God. If we find intelligent aliens out in the universe, then the Christian idea of the incarnation of Christ here on earth is debunked, for how could God care about us when the universe is teeming with all sorts of sentience? But likewise, if there are no intelligent aliens out there, then life on earth is obviously just an accidental by-product in the universe (79).

But what this red herring proponent gets wrong is the relation between value and size—specifically that size does not equal value. CSL notes that “if we are a small thing to space nd time, space and time are a much smaller thing to God.” (81). It would be weird if all of the giant universe were made just for us, but it isn’t, it’s made for God’s glory and delight. He says “Christianity does not involve the belief that all things were made for man. It does involve the belief that God loves man and for his sake became man and died.”(81-82).

But, but what about aliens again? How can we believe that God only visited our planet? What’s so special about earth that God would become an earthling and die on a cross for humans who trust in Him for the forgiveness of their sins? There is a whole huge, gigantic universe out there and if there are any other life forms, which there just have to be, then it doesn’t make sense that God would care so much about our planet and what I do in my puny life.

CSL replies to this objection by analyzing the three assumptions which it is predicated on:

It assumes:

1. That there are rational aliens like us elsewhere in the universe

2. that they are fallen creatures who are in need of redemption like us (CSL writes about unfallen aliens in the first two books of his Ransom Trilogy science fiction stories to combat this assumption)

3. that a fallen alien species must be redeemed in the exact same mode as our redemption

4. that redemption in this modes has been withheld from them.

But why think any of these assumptions are true?

CSL puts the final nail in the coffin to the immensity challenge to miracles by arguing that “Christ did not die for men because they were intrinsically worth dying for, but because he is intrinsically love, and therefore loves infinitely.” (82).

Why does God care about tiny beings like us on a pale blue dot, and so much so that He would enact as sorts of miracles in our human history? Because size does not equal worth and because He is awesome and loves us because He chose to, not because we’re exceptionally lovable, we’re not.

Ch. 8 – Miracles and the Laws of Nature

Chapter 8 is a thing of beauty! Not that the others aren’t as well, but man, this one is straight to the point and super easy to comment on—which is especially beautiful to me because I’ve had a long week and it’s only Tuesday.

In this chapter, CSL is engaged in what’s known as the philosophy of science, it’s like meta-science. What kinds of things are true given science, what kinds of things must be true if we are able to do science, etc. Scientific investigation often assumes the laws of nature, rather than directly studying them. But when you start to give a philosophical account of the nature of the laws of nature, you’re not doing science, as a first order discipline, anymore, you’re engaged in the philosophy of science. And that’s what CSL is doing here.

CSL says there are 3 views on the laws of nature:

1. The laws of nature are brute facts. They just are what they are and we can’t explain why they are the way they are.

2. The laws of nature are one application of the law of averages. “The foundations of Nature are in the random and lawless. But the number of units we are dealing with are so enormous that the behaviour of these crowds (like the behaviour of very large masses of men) can be calculated with practical accuracy.” (88)

3. Fundamental laws of physics are necessary truths, i.e., they cannot have been otherwise and they are true in every possible world.

Now CSL argues that (1) doesn’t rule out miracles, because if we don’t have an explanation for a thing, we have no reason to give for why it shouldn’t be otherwise, why it should be opposite what it is. And in that case, we don’t have a reason to think it won’t someday be other than it is. Meaning, brute facts can’t keep out miracles because we don’t know enough about them. Brute facts are mute facts, as Cornelius Van Til said.

Likewise, (2) doesn’t rule out miracles because it’s rooted in probabilities which are based on regular states of affairs. This view of the laws of nature can tell you that flipping a coin 1,000 times probably won’t come up heads 900 of those times, but that’s only if you’re flipping a fair coin. But CSL argues, in the case of a miracle the coin is not fair. If a loaded coin is thrown into the mix the laws of nature, pitched in this view, won’t be broken, but the result won’t be normal either.

CSL argues that upon first glance, (3) looks like it might conflict with the idea of miracles, but upon further investigation, it turns out not to. Laws as necessary truths, likewise carry an implicit ceteris paribus clause, that is with other things being equal or if there are no interferences, then such and such must be the case. But again, argues Lewis, in the case of a miracle, there is an interference taking place. If there are no interferences, then this billiard ball with hit that billiard ball with a predictable velocity and will pass on x amount of kinetic energy, etc., and while the law that describes that kind of event may be a necessary truth, the fact that those two balls will collide is not itself a necessary truth. How do I know? Because Steve can just reach down and grab the far ball before the cue ball hits it. The law remains unbroken and necessary, if (3) is the correct view of the laws of nature (which it is not), but an interference took place nonetheless. That’s CSL’s point.

Miracles introduce new factors into the situations which the laws of nature describe (92), and it is inaccurate to say that miracles ‘break’ the laws of nature—they don’t (94).

Lewis goes on to explain how a miraculous conception can happen,

“If God creates a miraculous spermatozoon in the body of a virgin, it does not proceed to break any laws. The laws at once take it over. Nature is ready. Pregnancy follows, according to all the normal laws, and nine months later a child is born.” (94).

CSL finishes up by telling us again what a miracle is not, “In calling them miracles we do not mean that they are contradictions or outages; we mean that, left to her own resources [nature] could never produce them.” (98).

I really love CSL’s teaching on what miracles are and aren’t in light of the three views of the laws of nature. I think it’s very helpful to see miracles not as a breaking of nature, but as adding in new information into nature. This idea fits nicely with my old systematic theology professor Kevin Vanhoozer’s view of divine action, i.e., that God interjects into nature instead of thinking of intervention. God spoke everything into being and upholds it by His Word. Miracles, then are just more speaking, throwing more information into the mix to bring about a different desired result to grab attention.

Also, CSL wrote chapters 7&8 for the original publication in 1947 and a lot of thought has gone into what the laws of nature are since then—a whole ton of philosophy of science has advanced! So, if you want to dive deeper, check out this article on the laws of nature from the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy: https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/laws-of-nature/

But let me know what you think! Leave me a like on this post so I know how many are actually reading-along with me. And leave me your thoughts and questions in the comments. Were these more enjoyable than the last 6 chapters?

Some ideas to add to Red Herrings:

RH1 - you note that our inductive reasoning, that nature is uniform and the future will be like the past, is what allows us to identify an anomaly or miracle. Our capacity for induction/inference is also part of CSL's earlier evidence for the supernatural!

RH2 - with the size argument, our insignificance in the grand scheme of things can still be true, but then it must also be true that the level of effort required by a God to enact miracles is commensurately insignificant. So to say "why would He spend time on us" is the same as asking why I would spend time holding the door for a random person. It's just instinctual, takes half a second, and is immediately forgotten. I guess what I mean is, the proportion with which a God Creator might think about us pales in comparison to how much we spend thinking about Him. Like in Toy Story, the boy is everything to the toys but he has so much more going on (such that they get thrown away, packed away, forgotten, lost).

I definitely felt pretty adrift in the last few chapters but 7 & 8 were really enjoyable and I felt like I was able to track with Lewis a lot better!

I really liked the section explaining how miracles don’t break the laws of Nature but conform to it.

Loved this section in particular:

“Miraculous wine will intoxicate, miraculous conception will lead to pregnancy, inspired books will suffer all the ordinary processes of textual corruption, miraculous bread will be digested.”