Arguing for God from Reason | ch. 3 of C.S. Lewis's Miracles

This One is Wild! They Will All Be Less Intense Than This Chapter!

Welcome to the Parker’s Ponderings read-along of Miracles by C.S. Lewis. This is the second companion essay in the series and in it I’ll be covering chapter 3 of the revised (1960) edition of the book. Initially I had planned this companion essay to cover chapters 3-6 since those chapters all focus on what has come to be known as CSL’s ‘Argument from Reason’ but that would be preposterously long. So, I’m breaking it up just a tiny bit and focusing solely on chapter 3 for this essay. I will post another companion essay later this week (hopefully Thursday the 10th) on chapters 4-6, but chapter 3 is the most difficult chapter in the book so it warrants its own essay.

I’ve revised the reading schedule to account for the change in the companion essays and because this latest one, with its more limited scope, is a day late (sorry about that, it took me much longer than expected and I had 2 jiujitsu tournaments over the weekend and I was way too naïve about what I could get done between those events).

I’ve asked my paid subscribers here on Substack for feedback on potential book club times—that is times for our first Zoom call where we will discuss chapters 1-6—and we’ve come up with a date and time! Our first book club session will be on Saturday, April 12th from 1pm to 2:30ish pm central time. This will be limited to paid subscribers so make sure to upgrade to paid if you want to be in on that (and get access to paid only essays and short stories as well). You will be able to find the Zoom link in our paid subscriber chat here on Substack or on Patreon or YouTube Members if you support me there.

Read-Along Schedule

March 31st - Chapters 1-2 – World-and-life views, presuppositions, and the philosophy of fact

April 9th - Chapter 3 – Three Arguments from Reason Against Naturalism

April 10th – Chatpers 4-6 – Four or Five More Arguments from Reason

Zoom Call for Paid Subscribers #1 – April 13th from 1:00pm – 2 or 2:30pm central

April 14th – Chapters 7-8 – common objections to miracles, the nature of nature, and what

miracles are not

April 21st - Chapters 9-12 – The Author Analogy, The Ultimate Fact, Doctrine of God

Zoom Call for Paid Subscribers #2 – to be determined

April 28th - Chapters 13-14 – Presuppositions and Argument from Reason revisited, Criterion of Miracles, a Theology of Religions

May 5th – Chapters 15-Appendix B – The True Myth, One vs. Two-Floor Realities, Against Monism, Author Analogy Revisited

Zoom Call for Paid Subscribers #3 – to be determined

Okay let’s get into Miracles Chapter 3

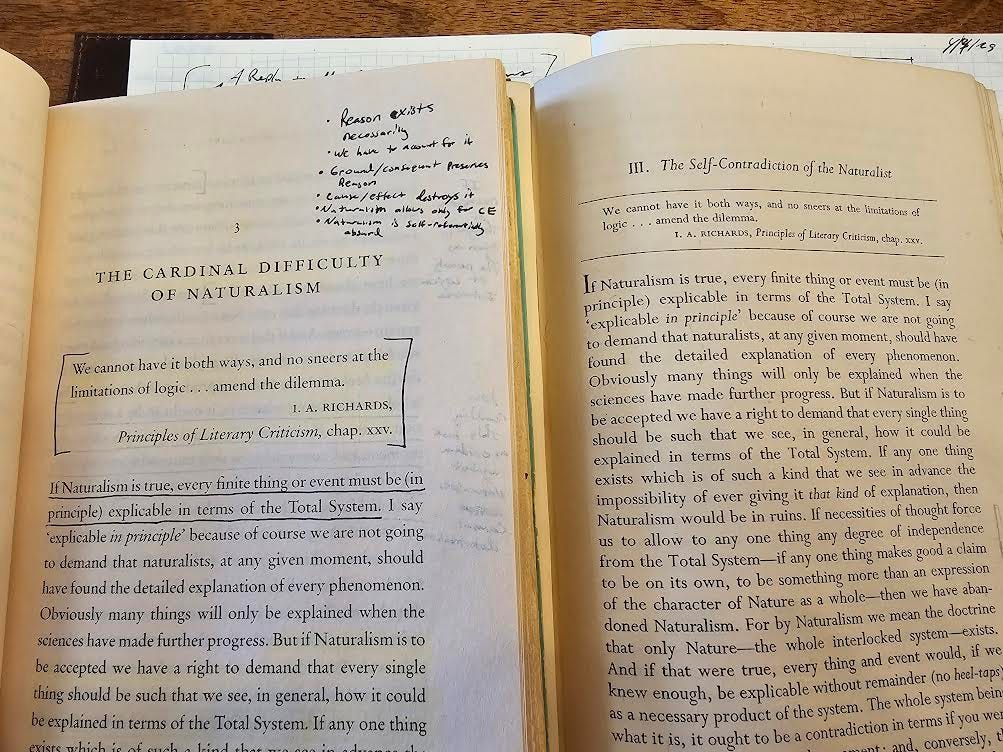

Chapter 3– The Cardinal Difficulty of Naturalism

The chapter 3 which you’ve read in the revised edition of CSL’s Miracles is the most difficult chapter in the whole book—so congratulations! You made it through the toughest one and the rest is smooth sailing (in comparison…). But really, if this one was not fun for you, don’t fret, it will get both easier and much more enjoyable. We’re going to have fun, I promise you! But not yet, this companion essay is about to get super arduous. I’m sorry.

Now chapter 3 is so difficult because CSL revised it in light of philosophical criticism leveled against it by philosopher G.E.M. Anscombe.

The original title of the chapter, published in the first edition of Miracles in 1947, was “The Self-Contradiction of the Naturalist”. Elizabeth Anscombe (aka ‘G.E.M.’) wrote a paper titled “A Reply to Mr C.S. Lewis’s Argument that “Naturalism” is Self-Refuting” wherein she argued that CSL’s argument in the original chapter 3 was “specious because of the ambiguity of the words “why”, “because” and “explanation”’.[1] She then presented this paper to the Socratic Club of Oxford, in front of CSL—who was actually the president of the club—and then they had a lengthy debate about her criticisms. The club secretary for that night noted that “From the discussion in general it appeared that Mr Lewis would have to turn his argument into a rigorous analytic one, if his notion of “validity” as the effect of causes were to stand the test of all the questions put to him.”[2]

So, CSL did just that. Based on the debate with Anscombe, he made his argument more ‘analytic’ and expanded the chapter out to include additional arguments as well. All in all, the book is better for it, even if the chapter is much more rigorous than a lay audience might enjoy.

A quick note on the Oxford Socratic Club:

The Socratic Club was a meeting of philosophers, literary critics, and other thinkers who got together to share papers on various topics and to then offer constructive criticism and have lively debates on the ideas presented. After the sessions, the papers were published, sometimes with replies from other thinkers, in a journal called Socratic Digest. CSL was the president of the Socratic Club from 1942 through 1954 when he left Oxford for Cambridge, upon which time philosopher Basil Mitchell took over. You can grab all the Socratic Digest issues from CSL’s time in this book here (which is an affiliate link of mine).

Now, I’d love to address the debate points between CSL and Elizabeth Anscombe in more detail but I can’t do that in this essay, we have too much to cover from the revised edition. From what I’ve heard, many in attendance sided with Lewis over against Anscombe. It’s also rumored that Anscombe’s husband, Peter Geach, a brilliant philosopher in his own right, also sided with CSL regarding his first version of the argument. But I digress—and I don’t have the space for it! So let me digress on the history of Lewis’s argument from reason, and the debate with Anscombe, and those down stream of CSL who’ve improved his argument in a different, bonus essay, dedicated to such stuff.

So, let’s get on with the actual chapter 3 which you read, which was revised after getting feedback from Anscombe and others (like H.H. Price—I’ll discuss his counter points in the forthcoming essay on the Arugment from Reason as well!) and published in 1960.

4 Arguments Against Naturalism

As far as I can tell, CSL levels 4 arguments against naturalism in the Cardinal Difficulty of Naturalism:

(1) Quantum Indeterminacy

(2) Ground-Consequent Reasoning (demonstratio quia)

(3) A Proto-Evolutionary Argument Against Naturalism

(4) A Retorsive Transcendental Argument with An Inference to the Best Explanation

Okay, so those words are scary and awful, but I’ll make it all perfectly clear(ish) and by the end of this post you’ll know what I’m talking about and will understand CSL better. So bear with me, we’ll take them one at a time.

(1) Quantum Indeterminacy

Both new and revised editions broach the idea of quantum indeterminacy as a potential problem for the particular flavor of Naturalism which CSL has targeted. CSL argues that if Naturalism is true then every thing and event, and whatever else exists, must be explicable (explainable) in terms of the Total System—at least in principle. That means that everything that exists must be able to be explained by the tenets of Naturalism. If we find that something exists which is impossible to explain on Naturalism, then Naturalism is false. Now there may be some things which are difficult to explain on Naturalism or which we can’t fully explain now but can imagine finding a more complete explanation to with more time and research, but if we find something that straight up doesn’t fit and completely resists a naturalistic explanation, then naturalism is false, or so argues CSL.

CSL suggests that perhaps quantum indeterminacy is one such phenomenon which resists naturalistic explanation in principle. On the third paragraph of page 18 (HarperOne edition), Lewis says:

One threat against strict Naturalism has recently been launched on which I myself will base no argument, but which it will be well to notice. The older scientists believed that the smallest particles of matter moved according to strict laws: in other words, that the movements of each particle were ‘interlocked’ with the total system of Nature. Some modern scientists seem to think—if I understand them—that this is not so. They seem to think that the individual unit of matter (it would be rash to call it any longer a ‘particle’) moves in an indeterminate or random fashion; moves in fact, ‘on its own’ or ‘of its own accord’. The regularity which we observe in the movements of the smallest visible bodies is explained by the fact that each of these contains millions of units and that the law of averages therefore levels out the idiosyncrasies of the individual unit’s behavior. The movement of one unit is incalculable, just as the result of tossing a coin once is incalculable[3]

CSL goes on to argue that “If the movements of the individual units are events ‘on their own’, events which do not interlock with all other events, then these movement are not part of nature.”[4] So the argument here is that Naturalism posits a Total System of Nature which consists of interlocking events, and that nothing exists outside of nature and even if it anything did exist outside of nature, it wouldn’t matter because anything outside would be locked out—nature is closed. This is known as physical causal closure, i.e, that all physical events have only physical causes. But if quantum indeterminacy is true, if the fundamental particles, or the wave function, or the super strings, or whatever is actually down there, then those things don’t actually abide by the laws of nature which govern the Total System of Nature, and they lead to physical events but aren’t physical things as they don’t abide by the laws of physics (?).

Now we shouldn’t press this point too hard, because CSL didn’t press it too hard as he acknowledged he was out of his depths, and if he was, then I certainly am and even worse so. But the point is that if quantum indeterminacy, then perhaps there are sub-natural things, like the fundamental entities of theoretical physics, which resist being explained by naturalism but which are fed into the system of Nature through the backdoor. To which CSL says “clearly if [Nature] thus has a back door opening on the Subnatural, it is quite on the cards that she may also have a front door opening on the Supernatural—and events might be fed into her at that door too.”[5]

So, according to CSL, if quantum indeterminacy, then nature is not causally closed to just events and causes which rigidly adhere to the laws of nature and which are explicable in terms of the laws of physics. And if nature isn’t causally closed, well then miracles can get in too… at least in principle.

(2) Ground-Consequent Reasoning (demonstratio quia)

CSL moves from a potential threat to Naturalism from quantum physics to what he takes to be a very serious threat from philosophy, particularly from epistemology—that is, from the study of knowledge.

Lewis argues that all possible knowledge depends on the validity of reasoning. If no reasoning is valid, that is, if no bit of reasoning ever logically follows from another bit, then all knowledge goes out the window. Thus, human reasoning is the most important phenomena to account for in one’s theorizing. If a theory can explain everything in the universe but it logically entails that our minds can’t actually form valid arguments with true premises, and conclusions which follow from them, then that theory must be false. It would be like giving “a proof that there are no such things as proofs—which is nonsense.”[6]

Now up until the end of the first paragraph on page 22 of the HarperOne edition, both the original 1946 chapter and the 1960 chapter are exactly the same. However, in the first edition, CSL went out to discuss ‘irrational’ causes of belief and how they destroy any claim to knowledge, arguing that if Naturalism were true, then all of our beliefs would have been produced by irrational causes, including our belief in Naturalism. But it’s here that CSL makes his ‘analytic’ changes to the revised edition by discussing two senses of the word ‘because’:

Sense 1: Cause & Effect ‘because’ (CE-because)

CSL argues that this CE sense of because is a dynamic relation between events or states of affairs and gives the examples: “he cried because it hurt him”[7] and “‘Grandfather is ill today because he ate lobster yesterday.’”[8] This is a straight forward explanation following a linear causal chain. Someone cried because they got hurt, someone is sick because they ate bad lobster. Cause and effect.

Sense 2: Ground & Consequent ‘because’ (GC-because)

CSL argues that this GC sense of because is a logical relation instead of a relation between events or states of affairs. Here we’re not following a causal chain of physical causes but we’re reasoning from a consequence to its ground. Here CSL gives the examples of “it must have hurt him because he cried out”[9] and “‘Grandfather must be ill today because he hasn’t got up yet (and we know he is an invariably early riser when he is well)’”.[10]

Now CSL didn’t make up these distinctions whole cloth, he’s actually pulling from logicians (experts in logic), both medieval and modern. Logician John Corcoran explains that, according to another logician, Bernard Bolzano, the ground-consequence relation is a particular kind of logical relation where “A is the ground of B (and B the consequence of A) when A and B are both true and A is the “reason why” B is true.”[11] Bolzano further argues that a ‘ground-judgment’ relation also holds wherein “the relation often goes in the opposite direction from the ground-consequence relation, i.e., that A is sometimes the ground of B (the “reason why” of B) when in fact B is “the cause of our knowledge” of A.”[12] Corcoran goes on to give a similar example to those CSL gave in his GC-because explanation: “For example, we know that it is hot outside because we know that a certain thermometer reads high but the reason why the thermometer reads high is because it is hot outside.”[13]

I refer to this GC-because as demonstratio quia reasoning based on an obscure line from philosopher-theologian William Lane Craig in the Zondervan Fives Views on Apologetics book. Craig is responding to John Frame, the representative of the presuppositional apologist view, and says, “Unfortunatlely, Frame fails to develop for us [a transcendental] argument. Instead, he confuses transcendental reasoning with what medieval called demonstratio quia, proof that proceeds from consequence to ground.”[14]

So Lewis’s GC-because tracks with Bolzano’s ground-consequence relation and his ground-judgment relation. We can reason from B to A, from consequent to ground (demonstratio quia above), because A is the reason why B is true. So, we can reason that grandfather must be ill today because he hasn’t got up out of bed yet, and he always gets up out of bed early when he’s feeling well. We’re reasoning from the consequence, grandfather is still in bed, to the ground, grandfather is ill. We reason from the consequent “he cried out” to the ground “it must have hurt him”.

Okay, so that’s a lot—too much surely. But here’s the upshot: we reason this way, at least sometimes, and we must have this ability to reason from consequent to ground and make other logical connections, finding reasons and logical entailments etc., if we are to have any knowledge whatsoever. We must be able to use GC-because and not be limited solely to CE-because if we’re going to be rational beings who know things and whose theories are truth-tracking. But, argues CSL, if Naturalism is true, “every event in Nature must be connected with previous events in the Cause and Effect relation. But our acts of thinking are events. Therefore the true answer to ‘Why do you think this?’ must begin with the Cause-Effect because.”[15]

So if Naturalism is true, then all events are cause and effect events, including our thoughts, and thus our thoughts could never be the result of a ground and consequent relation, which seems to rule out sound reasoning. But if Naturalism rules out the ability to reason, then we can’t use reason to affirm Naturalism—it’s a self-defeating theory in that case.

So, the naturalist’s physically causally closed interlocking system of Nature keeps out the possibility of miracles but it also makes all events physically causal events and precludes ground-consequent relations and would wreck our ability to reason, so naturalism must be false (so the argument goes).

There’s also a little bonus argument in the last paragraph on page 25 where CSL argues that while acts of thinking are events, they are “a very special sort of events. They are ‘about’ something other than themselves and can be true or false.” This ‘aboutness’ is a really special property of thoughts and propositions called ‘intentionality’ in the philosophy of language and the philosophy of mind. The fact that physical things aren’t ever ‘about’ anything else but that thoughts are about their contents has been used to argue that since thoughts have different properties than physical things, thoughts cannot be reduced to physical things, and thus physicalism about the mind, or the self, or the subject, is false. It’s much more nuanced than that but this post is already too long. Anyways, It’s pretty incredible to find this kind of reasoning in a popular-level book on miracles from 1960 written by a non-academic philosopher.

I get that Lewis and I are throwing around a lot of dumb words and I bet that’s confusing, but Lewis also throws in a really helpful quote from JBS Haldane on page 22 which should clear up his argument a bit:

If my mental processes are determined wholly by the motions of atoms in my brain, I have no reason to suppose that my beliefs are true…and hence I have no reason for supposing my brain to be composed of atoms.[16]

CSL argues that even if Naturalism isn’t wholly materialistic (or physicalist), it suffers from the same kind of problem that Haldane notes: if the universe is causally closed like the Naturalist posits, then all of my beliefs are wholly determined by physical causation and have a CE-because explanation. But physical causes aren’t the kinds of things that can produce true beliefs. Instead, we need good reasons to serve as justification for our beliefs, we need GC-because explanations. If, at the end of the day, your beliefs are the products of the non-rational forces of nature acting on your brain to produce the beliefs you have, then whether or not those beliefs are true is irrelevant. If you have a true belief, you received it by chance or accident, but not because you’ve seen it to logically be the case or because you had a flash of rational insight. Reason doesn’t come into the picture here if physical causes are the ultimate cause of your beliefs.

So very bluntly, if Naturalism, then the rational justification for your true beliefs is drained away since the ultimate explanation for your beliefs is a non-rational chain of physical causes instead of a logical chain of inference. [Check out this great paper by my former professor on Mental Drainage, it’s the best version of the Argument from Reason so far: Rickabaugh's Mental Drainage ]

(3) A Proto-Evolutionary Argument Against Naturalism

Here I’m picking out Lewis’s argument against naturalistic evolution present in chapter 3 and calling it a ‘proto’ version of Alvin Plantinga’s Evolutionary Argument Against Naturalism (EAAN). I will talk about the connection between Plantinga’s EAAN and Lewis’s Argument(s) from Reason—and how both owe a serious debt to Arthur James Balfour—in that bonus post that I mentioned above. But for now, I’ll just note that CSL just briefly mentions what Plantinga goes on to argue for in rigorous analytic fashion with Bayesian probabilities. The main contention is not that evolution is false but that the conjunction of Naturalism and evolution would more likely produce cognitive faculties that are aimed at surviving rather than at finding truth. And if that’s the case, then we couldn’t trust our own cognitive faculties to provide us with true beliefs rather than beliefs that are advantageous for survival. But then we wouldn’t have any reason to think Naturalism is true.

CSL starts his argument on the bottom of page 27 of the HarperOne edition and runs it through page 31. Lewis argues that “for the Naturalist, this process [of the gradual evolution of human cognition] was not designed to produce a mental behavior that can find truth. There was no Designer; and indeed, until there were thinkers, there was no truth or falsehood.”[17] Naturalistic evolution, Darwinistic, unguided evolution, agues CSL, has as its aim survival, and the process would likely lead to a conditioning of the human mind to form beliefs that are biologically advantageous, indeed the whole process might not even need to access the human intellect at all,

Such perfection of the non-rational responses, far from amounting to their conversion into valid inferences, might be conceived as a different method of achieving survival—an alternative to reason. A conditioning which secured that we never felt delight except in the useful nor aversion save from the dangerous, and that the degrees of both were exquisitely proportional to the degree of real utility or danger in the object, might serve us as well as reason or in some circumstances better.[18]

So either Naturalistic evolution, which is unguided and not designed and aimed at producing true beliefs per se, but at the survival of the species, would either produce cognitive faculties which themselves produce beliefs which are advantageous for survival, but not necessarily true beliefs, or it would work around the cognitive faculties all together and condition responses in the organism which don’t require prolonged rational reflection at all. CSL’s point is that both of these options are more plausible on Naturalism than that we have the ability to reason and reach truths by inferences.

The natural response of the Naturalist is to say “it is incontestable that we do in fact reach truths by inferences”[19] though, to which Lewis responses: “Certainly”. The argument is that if Naturalism were true, naturalistic evolution wouldn’t produce the cognitive faculties we take ourselves to have, faculties which allow us to reason well and find truth and gain knowledge with logical inference, so Naturalism can’t be true if we’re able to reason.

Again, this is a really thorny issue and there’s been a lot of ink (and digital ink) spilled over it. I won’t solve all of those issues here, though I may broach them in the bonus piece. For now let me just give an intuitive analogy for those who are lost.

Think of a bullfrog, let’s name him Bill. Imagine that Bill the bullfrog has self-reflective thoughts. Bill thinks that if he just eats one more dragon fly, then he will transform into a human prince. Now that thought is false. Bill won’t be transmogrified into any human prince no matter how many dragonflies he eats. But if Bill continues to believe that falsehood, he will continue to put himself in a position to survive. That belief is advantageous for Bill’s survival even though it is utterly false. Now true beliefs are hard to come by, there is only one right answer to the equation, but there are tons and tons of wrong answers which are ‘close enough’ for survival. As CSL’s argument goes, the unguided process of naturalistic evolution would much more likely produce cognitive faculties which produce false beliefs like Bill the Bullfrog’s frog-prince belief than truth beliefs. Or, maybe even more likely for CSL, the naturalistic process would bypass self-reflective thoughts and the mind all together and opt for a non-rational like conditioning movement based on stimuli.

(4) A Retorsive Transcendental Argument with An Inference to the Best Explanation

CSL’s 4th argument in the revised chapter 3 can be seen as a negative transcendental argument or a retorsive transcendental argument with an inference to the best explanation. Another string of insane words, I know! But we’re almost through the chapter and this impossibly long companion essay.

A transcendental argument is an argument that takes a given of human experience like consciousness, or speech, or the ability to reason, and asks what must be the case for this experience to be what it is? What are the necessary presuppositions or preconditions which must be the case for this aspect of human experience to exist at all? So we have human experience X, that’s the given, but what must be true if X is possible? Well, if X is possible, then Y must exist because Y is a necessary precondition of X. So, Y exists. Here’s a quick example, humans can argue with each other. What’s a necessary condition (or precondition) which makes human arguments possible? One would be the ability to use language. So if two humans are able to argue (or not argue), then they must have the ability to use language.

Now for the word “retorsive”. A retorsive transcendental argument would prevent the skeptic from denying the given of experience in view, which forces the skeptic to entertain the rest of the transcendental argument. According to TA theorist Robert Stern, “such arguments have been called “retorsive” from the Latin “retorquere”, meaning to twist or bend back, referring to the way in which such arguments “turn back” the sceptics own position against her.”[20] A quick google search indicated that retorquere is also the same root of ‘retort’.

So a retorsive starting point of a TA is one that will turn or twist or bend back on the skeptic if they try to deny it. A good example of a retorsive TA comes from Aristotle’s defense of the fundamental law of logic known as the Law of Noncontradiction[21] in his Metaphysics. The law of non-contradiction states that something can’t both be and not be in the same way at the same time. So, not both A and ~A at the same time and in the same manner.

The Law of Noncontradiction cannot be proven through direct argument such as using a modus ponens (if A then B, A, therefore B)- since any argument must presuppose the Law of Noncontradiction. But it can be proven indirectly since argumentation is possible and a precondition of argumentation is the Law of Noncontradiction.[22] So here we’ve found another precondition for the possibility of arguments along with the ability to use language.

I. Argumentation is possible

II. A precondition of argumentation is the Law of Noncontradiction

Therefore,

III. The Law of Noncontradiction obtains

This TA is retorsive in that the skeptic cannot deny premise I, for in denying it, they are arguing against it, showing that argumentation is in fact possible.

So I think Lewis is setting up a retorsive transcendental argument against Naturalism. Reason, as the ability to find truth, and gain knowledge through logical inference, exists. You’d have to use Reason to try and deny Reason, thus proving Reason indirectly. It’s a given of human experience that we can Reason. CSL says,

If the value of our reasoning is in doubt, you cannot try to establish it by reasoning. If, as I said above, a proof that there are no proofs is nonsensical, so is a proof that there are proofs. Reason is our starting point. There can be no question either of attacking or defending it. If by treating it as a mere phenomenon you put yourself outside it, there is then no way, except by begging the question, of getting inside again.[23]

So, Reason exists as the starting point of all thought. You cannot directly prove it, though it can be indirectly proven by the fact that you can’t even try to disprove Reason without presupposing Reason.

From the starting point of Reason, Lewis argues that Naturalism cannot account for it, by appealing to his proto-EAAN argument and his ground-consequence argument, cited above. But he goes on to argue on page 36 that the Naturalistic accounts of Reason always tacitly presuppose a stronger view of Reason than their picture would allow, a view like the supernaturalist’s view of Reason where Reason is free from non-rational causation and where knowledge is determined only by the truth it knows rather than by past physical events and the laws of nature.

So Lewis starts with Reason, which includes logical inference but probably includes more than just logical inference for him, and seeks to show that the naturalist’s position denies logical inference, but logical inference cannot be denied, for in denying it, one affirms it. So then the argument retorts back on the Naturalist providing a reductio ad absurdum. So Naturalism is false.

But while CSL seeks to give a negative argument against Naturalism from Reason, he also goes on to give a positive argument for supernaturalism by arguing that it provides a better explanation of Reason. Here CSL is employing what’s called ‘abductive reasoning’ or inference to the best explanation. CSL leans a bit on Augustinian divine illumination to account for a theistic view of Reason on page 34:

For [the theist], reason—the reason of God—is older than Nature, and from it the orderliness of Nature, which alone enables. Us to know her, is derived. For him, the human mind in the act of knowing is illuminated by the Divine reason. It is set free, in the measure required, from the huge nexus of non-rational causation; free from this to be determined by the truth known. And the preliminary processes within Nature which led up to this liberation, if there were any, were designed to do so.[24]

So CSL argues that Reason is our starting point, we are stuck with it unless we jump into irrational lunacy to avoid it. As such, our metaphysical theories, our world-and-life-views, must be able to account for Reason. But Naturalism cannot account for reason and even tries to denigrate Reason, but in so doing, the naturalist actually presupposes the stronger view of Reason which we all operate by. Theism, a supernaturalist view which says God exists and is the creator of all, gives a better explanation for human reason, arguing that God’s Reason came before Nature and that Nature is orderly and intelligible because it was created by a rational being. When human beings use their created reason to find God’s truth in reality, their minds are illuminated by the Divine reason. Another way to put it is that humans are thinking the divine thoughts after Him, discovering the truth that He put out there in the world. CSL finishes by arguing that either God specially created the human mind or the natural processes which gave rise to the human mind were designed to develop the human mind to find God’s truth in Nature. Thus if evolution is the process that developed out cognitive faculties, a theistic process of evolution would be guided by God to give humans cognitive faculties which could reason like Him and find his truth whereas an unguided naturalistic evolutionary process would be aimed at survival rather than at truth, per se.

Okay. Wow. That was a slog! But you made it and really, the rest of the book is more enjoyable! I look forward to seeing my paid subscribers this Saturday for our Book Club Zoom call on chapters 1-6. If you want to join then upgrade to paid before then and look for the Zoom link in the next few days in the paid subscriber chat. Hopefully I’ll have the companion essay on chapters 4-6 out tomorrow, but definitely by Friday.

[1] G.E.M. Anscombe, “A Reply to Mr C.S. Lewis’s Argument that “Naturalism” is Self-Refuting” in Metaphysics and the Philosophy of Mind: Collected Philosophical Papers Volume II (Oxford: Basil Blackwell Publisher, 1981), 225.

[2] Ibid., 231.

[3] C.S. Lewis, Miracles: A Preliminary Study (New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 2001), 18-19.

[4] Ibid., 19.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ibid., 22

[7] Ibid., 23.

[8] Ibdi., 22.

[9] Ibid., 23.

[10] Ibid., 22.

[11] John Corcoran, “Meanings of Implication” in A Philosophical Companion to First-Order Logic ed. R.I.G. Hughes (Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Company, Inc., 1993), 97.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Ibid., 97-98.

[14] William Lane Craig, “A Classical Apologist Response [to presupp]” in Five Views on Apologetics ed. Steven B. Cowan (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2000), 233.

[15] C.S. Lewis, Miracles: A Preliminary Study (New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 2001), 23.

[16] Ibid., 22.

[17] Ibid., 28.

[18] Ibid., 29.

[19] Ibid., 31.

[20] Robert Stern, “Silencing the Sceptic?” in Transcendental Arguments in Moral Theory, ed. Jens Peter Brune, Robert Stern, Micha H. Werner (Berlin/Boston: Walter de Gruyter GmbH, 2017) 11.

[21] Formerly called “the Law of Contradiction*”

[22] “Aristotle’s “elenctic refutation” has been fruitfully compared to a Kantian transcendental argument. Transcendental arguments generally run as follows: If certain aspects of experience or thinking are possible, the world must be a certain way. Since these aspects of experience or thinking do exist, the world is a certain way. These aspects of our experience or thinking presuppose that the world is a certain way. That the world is a certain way explains these aspects of our experience or thinking and not the other way round. On this interpretation, Aristotle would be arguing that the world conforms to PNC, or that PNC is true, because it is presupposed by and explains the opponent’s ability to say something significant.” Gottlieb, Paula, "Aristotle on Non-contradiction", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2019 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), URL = <https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2019/entries/aristotle-noncontradiction/>.

[23] C.S. Lewis, Miracles: A Preliminary Study (New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 2001), 33.

[24] Ibid., 35.

I am moving on to 4-6, but I will definitely be circling back to chapter 3. I think I understand the basics but I will spend more time breaking these ideas down.

Thanks for making these ideas so clear. I noticed I’d highlighted the same passages in my own reading, but your article really helped me see the glow of the arguments which is most critical. On my own, I only had a vague sense of the discussion—it’s your writing that brings it into focus.

I do have a question, though: couldn’t the ‘randomness’ we observe in quantum inference simply be the inherent nature of the system? Why do we need to rationalise or account for this randomness, rather than just accepting it as part of the system’s basic entropy or maybe even an unintelligible event that sets the chain of rational events? is there any flaw in this argument?