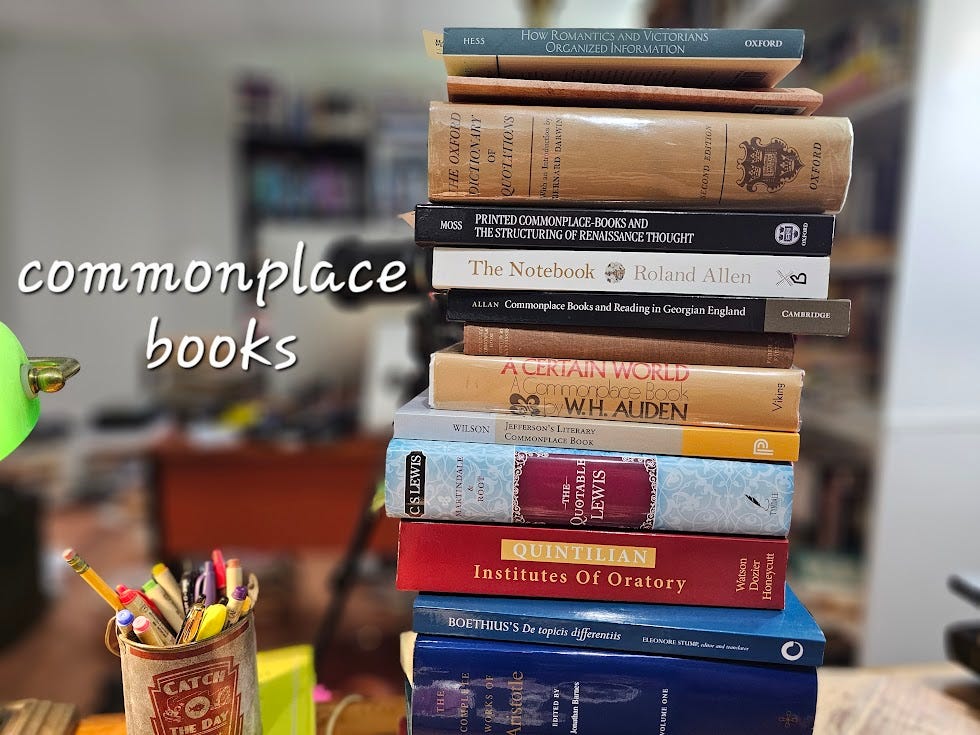

What is a Commonplace Book?

Commonplace Book Definitions, Examples, and All the Ways to Keep Your Own

In this post, I’m going to provide some definitions of ‘commonplace book’ from academic sources (including from Herman Bavinck!); I’ll show you some examples of published commonplace books like founding father Thomas Jefferson’s, poet W.H. Auden’s, and philosopher George Berkeley; I’ll give my own working definition from my own forthcoming book, Journal Like a Philosopher; and then I’ll give you my most up-to-date categories for picking the best kind of commonplace book for you.

I’m giving you a taste of the article but you’ll end up running into a paywall. These notebook philosophy posts are basically the first drafts of my forthcoming book, Journal Like a Philosopher. One of the perks I offer my paid subscribers is getting a first look at the contents of the book and giving paid subscribers an opportunity to provide feedback so that the final form of the book helps them more than it would have otherwise. The final book will be fleshed out much more and include more quotations and in-depth work on various philosophers, but I’ll be working off and adding to these notebook philosophy posts here on Parker’s Ponderings.

Paid subscribers also get access to my digital commonplace book of wise sayings, access to my full catalog of notebook philosophy essays, access to the paid subscriber chat, access to my digital intro to philosophy text book, priority direct message replies, and a whole lot more. So if any or all of that sounds good to you, and you want to help support my work, upgrade to a paid subscription. That would be huge!

What is a Commonplace Book?

I’m prepping for a conversation with

on commonplace books this week. It’s going to be awesome! She’s literally a scholar of commonplace books. If you have questions you want me to ask her, drop them in the comments and see her Oxford University Press book, on commonplace books here.But as I’m prepping for our conversation, I can’t help being a little amazed at how many people want to think and talk about commonplace books. My YouTube videos on the topic get hundreds of thousands to millions views. Which is insane!

If you know anything about my YouTube presence, especially my ParkNotes channel, then you know I’m an accidental notebook czar. I didn’t ask for this, it sought me out and I’ve begrudgingly accepted the title. No matter how much philosophy and theology work I do, no matter how much time I spend writing poems and science fiction stories, none of it will ever outshine my notebook stuff. That’s alright, though, I’ve made peace with that and I’ve learned to Trojan-horse deep philosophy and theology into my notebooks content. I am a notebook czar.

Now, if I’m being completest here, I’m probably still more of a ‘frog czar’ thanks to my viral giant African bullfrog video from 2015 but thankfully my ParkNotes channel is finally starting to catch up to that video.

But back to the notebooks. As a notebook czar, I have access to tens of thousands of comments and questions from YouTube users about notebook methods—especially commonplace books. A lot of my commenters think a commonplace book is just a sort of hodgepodge notebook of miscellany. A ‘commonplace’ for all sorts of ideas and recipes and to-do lists, and more.

Now that style of notebooking where you just have one notebook to drop everything into is kind of cool, but it’s not a commonplace book—it’s probably more of a zibaldone notebook or a catch-all notebook (if it’s including actionable tasks). But ‘commonplace’ doesn’t mean the notebook is a ‘common place’ for everything. In some of my earliest ParkNotes videos I’ve called them “commonplaces for quotes and commonplaces for ideas” and that wasn’t right either (a commonplace for ideas notebook is a compendium). A commonplace book is a sort of common place for quotations but that’s not how it got its name.

The term ‘commonplace’ actually goes all the way back to Aristotle and initially referred to common headings used to categorize different argumentation schemes. I’ve gone over the history of the concept in in more detail in other posts. Check this one for a brief history here:

Now the original Greek term, koinoi topoi (loci communes in Latin), common-places, can be traced back to Aristotle, though he attributed it to philosophers before him. Aristotle’s commonplaces were heads or headings which represented common forms of argument. Aristotle was creating a sort of compendium of argumentation, with headings to help the reader study the argument more easily. A compendium is a detailed, comprehensive, collection of information systematically presented. More on compendiums here:

But the Roman rhetoricians and philosophers—especially Cicero and Quintilian—expanded Aristotle’s notion of commonplaces to include quotations of sententiae from respected philosophers and rhetoricians to serve as example cases. So instead of just having the rule or argument under a heading, you’d also have an example of the rule in a quotation from an authoritative source—e.g. “here’s this argument form and here is is in the being used by a notable philosopher”.

It’s this expanded notion of ‘commonplace’ as involving quotations that moved on into Western history and transformed into the commonplace book—a book of collected quotations.

However, even this expanded notion of commonplace book as ‘an organized collection of sententiae quotations’ is not actually all that new—in fact, it’s actually a super old tradition tracing back at least to King Solomon who reigned as king of Israel from 970 to 931 BC!

King Solomon made a commonplace book of proverbs and other sententiae which we call The Book of Proverbs, or just Proverbs for short. Solomon collected the sayings of the wise, including his own sayings, and stored them all in one book in order to teach his sons, and his nation by extension, wisdom. Ecclesiastes 12:9 says

“Besides being wise, the Preacher [Solomon] also taught the people knowledge, weighing and studying and arranging many proverbs with great care.”

I would so love for something like that to be written on my gravestone!

For more on King Solomon’s commonplace book, see the following post:

Definitions

My working definition:

A commonplace book is a collection of quotations which may or may not be arranged according to ‘commonplaces’ or common headings, and which is organized according to a particular scope and purpose, for a particular audience.

This is my latest and greatest definition wherein I’m trying to hit on all four differentia which I use to categorize the different kinds of commonplace books:

scope

purpose

places

audience.

More on that in the last section below.

For now, let me show you some of the commonplace quotes I’m pulling from:

“In the strictest sense, the term “commonplace book” refers to a collection of well-known or personally meaningful textual excerpts organized under individual thematic headings. These passages, or sometimes simply the headings themselves, have historically been termed “commonplaces”’. Earl Havens, Commonplace Books: A History of Manuscripts and Printed Books from Antiquity to the Twentieth Century, 8.

“We should imitate bees and we should keep in separate compartments whatever we have collected from our diverse reading, for things conserved separately keep better. Then, diligently applying all the resources of our native talent, we should mingle all the various nectars we have tasted, and turn them into a single sweet substance, in such a way that, even if it is apparent where it originated, it appears quite different from what it was in its original state.” -Seneca, quoted by Ann Moss, Printed Commonplace-Books and The Structuring of Renaissance Thought,12.

“Commonplace books also differed markedly in the purpose for which they were created.