What's A Ruler without Wisdom, Justice, and Prudence? | The Philosophy of Dune

Dune Read-Along Companion Essay 2

Welcome to the Parker’s Ponderings Dune in June (and some of July) Read-Along. This is the second of six companion essays I’m writing for those reading through Dune with me. Mostly, this read-along is a great excuse for all of us to visit or revisit Frank Herbert’s magnum opus, Dune. But I will also be writing these companion pieces to help us think about some of the deep lessons and philosophical sententiae that Herbert interlaced throughout the story. I’ll try and find a main through-line to explore for each essay and then I’ll more sporadically treat some of the wise sayings and subpoints.

I’m looking forward to hearing from you all as well, so make sure to leave your own thoughts and favorite quotes from the sections in view down in the comments.

Here’s the reading schedule:

June 5th – pages 1-105, read until this epigraph “Over the exit of the Arrakeen landing field, crudely carved as thought with a poor instrument, there was an inscription…” and the first line of the main text: “The whole theory of warfare is calculated risk…”

June 12th – pages 106-205, stop before epigraph “There should be a science of discontent…” and the first line: Jessica awoke in the dark, feeling premonition…”

Zoom Book Club – TBD

June 19th – pages 206-305, stop before the epigraph “At the age of fifteen, he had already learned silence” and the first line: “As Paul fought the ‘thopter’s controls…”

June 26th – pages 306-407, stop before the epigraph “The concept of progress acts as a protective mechanism…” and the first line: “On his seventeenth birthday, Feyd-Rautha Harkonnen killed…”

Zoom Book Club – TBD

July 3rd 408-515, stop before the epigraph “When law and duty are one, united by religion…” and the first line: “The smuggler’s spice factory…”

July 10th – pages 516-616 (the end of the book, before appendices)

Zoom Book Club – TBD

If you like my work and want to support it/get access to exclusive content and access the Zoom book club sessions, consider becoming a paid subscriber:

Of, if you just want to say a one-time thanks, consider buying me a coffee:

Paul: The Philosopher-King? - Essay 2

I was a little nervous about writing this second essay. Our second block of reading is less ‘philosophical’ than the first block, at least superficially, so I wasn’t quite sure what philosophical theme I was going to be able to write about. At first, I thought this section was just about the character development of Duke Leto, the just. But as I thought more about what happened with the other characters, it hit me—Herbert is doing something really fascinating and he’s a genius! This second reading is all about the erosion of the world supporters, those who are meant to guide Paul into the ideal leader—the messiah and philosopher-king!

Okay, so just follow me here and let me know if I’m onto something or just going nuts. Remember back to that key sententia (wise saying) from the Reverend Gaius Helen Mohiam about the four things which support worlds:

“A world is supported by four things… the learning of the wise, the justice of the great, the prayers of the righteous and the valor of the brave. But all of these are as nothing… without a ruler who knows the art of ruling. Make that the science of your tradition.” (38)

I’m starting to think this quotation is the key that unlocks the entire book!

About 20 pages after the quote above, Paul identifies Duncan as “the moral” and Gurney as “the valorous”, and he specifically makes reference back to the Reverend Mother’s saying: “Gurney’s one of those the Reverend Mother meant, a supporter of worlds—“…the valor of the brave.” (58).

Now, it’s obvious that Thufir Hawat is “the wise”, as the mentat councilor to three generations of Atreides, and that Duke Leto is “the just”, as his just character is on display as the juxtaposition of the vicious, unjust character of Baron Vladimir Harkonnen. Leto as matador; the Baron as bull.

So, we see that Herbert has personified four virtues:

Wisdom = Thufir Hawat

Courage = Gurney Halleck

Justice = Duke Leto Atreides

Temperance/Moral = Duncan Idaho

These four virtues just so happen to be the four cardinal virtues! Sometimes they’re called the four ‘Stoic virtues’ because of how the Stoics prized them and emphasized them in their teachings. But we also find them in Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics and most importantly, for our case, in Plato’s The Republic. I don’t know why I hadn’t caught this in any of the other times I’ve read through Dune—I guess I just thought the Reverend Mother’s sententia was a standard truism that Herbert was using to establish her as a sagacious old witch.

But upon reflection, and with the addition of the end of the quote—“But all of these are as nothing… without a ruler who knows the art of ruling. Make that the science of your tradition”—I’m pretty sure Herbert is referring to Plato’s Republic and the idea of the philosopher-ruler (often called the philosopher-king). Plato says, through his mouthpiece Socrates,

“The society we have described can never grow into a reality or see the light of day, and there will be no end to the troubles of states, or indeed… of humanity itself, till philosophers become kings in this world, or till those we now call kings and rulers really and truly become philosophers, and political power and philosophy thus come into the same hands, while the many natures now content to follow either to the exclusion of the other are forcibly debarred from doing so.” (Plato, The Republic, Penguin Classics, 191-92)

A well-ordered state, like a well-ordered self, will be virtuous, that is, wise, courageous, just, and temperate. An ideal state will be run by a philosopher-ruler who embodies those four cardinal virtues. Paul is the ideal candidate for becoming this virtuous ruler who knows the art of ruling as he is heir to the duchy of Caladan and Arrakis and is surrounded by four councilors, each of whom is a personification of one of the four cardinal virtues.

Additionally, Paul is brimming with immense potential—"terrible purpose” as he calls it. He could be the Bene Gesserit’s Kwisatz Hederach (an homage to the Hebrew word Kefitzat Haderech, which means “a shortening of the way”, which is referenced explicitly by Liet Kynes on page 166), the one who can be many places at once, who can see all of the collective unconscious—masculine and feminine—and guide humanity forward. He has the ability to sense truth, an instinct for rightness, and has premonitions in his dreams. Paul also has mentat capabilities and has been groomed his whole life to be a mentat-duke. He’s already one of the best fighters in the imperium, being trained by Duncan Idaho and being able to fight Gurney Halleck to a stalemate. He’s a cousin to the emperor, so he has a royal lineage. And he’s the current Ducal Heir to Arrakis and Caladan.

And if all of that weren’t enough, we found out in our second reading that Paul may also be the Fremen’s prophesied messiah as well, their Mahdi—which is a reference to the Muslim idea of an eschatological savior, a spiritual leader who will rule just before the end of the world and who restore religion and rid the world of injustice and evil before the return of Jesus.

Additionally, Paul could very well be the Fremen's Lisan al-Gaib, their foretold Voice from the Outer World—a Christlike figure foretold by the legend of the Missionaria Protectiva—the propaganda wing of the Bene Gesserit who seed worlds with legends that their sisters can utilize for their own protection when in need. The Lady Jessica, in turn, is seen as a type of Roman Catholic version of the Mother Mary figure—not being a virgin but being unmarried.

So Herbert is really building up his über philosopher-king messiah figure here, blending the ideals of Greek philosophy (through the 4 cardinal virtues), Judaism & Jungian pscychology (Kwisatz Haderach: shortening of the way & collective unconscious), Islam (Mahdi), Christianity (Lisan al-Gaib), process philosophy (mentat) and maybe others I've missed.

However, things are not going great for the budding philosopher-king. Three out of the four virtues are subverted in the course of our reading, each of which has some connection to the Lady Jessica:

Duncan, the Temperate/moral is asked to do something immoral: to spy on Lady Jessica. He goes home with a call-girl and gets drunk on spice beer then returns to the castle and drunkenly slanders the Lady Jessica, calling her a spy and blowing his cover.

Hawat, the Wise, has his mentat capabilities compromised by the pressure of the multitudinous Harkonnen threat and in his distrust of the Lady Jessica. He is unable to listen to Jessica’s reason and change his mind about her, instead he is stuck in a pattern of logic-chopping—demonstrating that intelligence and wisdom are not the same thing as he uses his powerful intellect to dig in deeper into his mistrust instead of properly weighing the evidence and listening to her voice of reason.

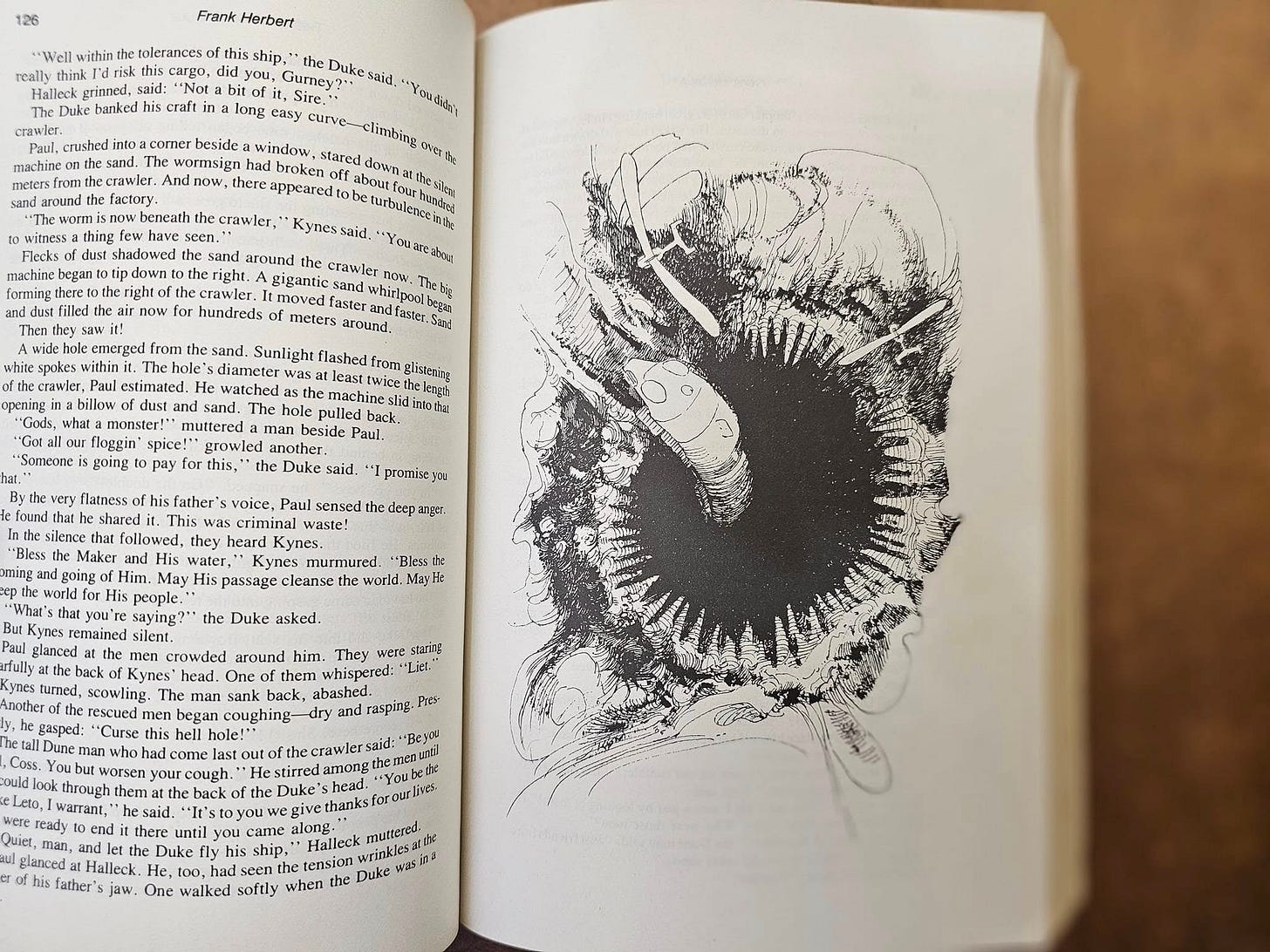

Duke Leto, the Just, falters in his justice. Leto becomes “morally tired” (132) from being hounded by Harkonnen plots—which are due in part to his declaration of kanly, that is, full-blown vendetta family warfare. Vendettas themselves being inherently unjust, punishing family members for the sins of their relatives and going above and beyond what is just retribution. Leto engages in subterfuge as he pretends to mistrust his Lady Jessica. He also instructs his men to forge signatures of loyalty over Harkonnen loyalist’s documents, acknowledges that he intentionally utilizes propaganda against the population of Arrakis, wins loyalty through cultivating an air of bravura, claims that the Atreides need to make their own justice, confesses to being morally fatigued and slipping, and encourages Paul to capitalize on the presumably false prophecy of the ‘Madi’ and ‘Lisan al-Gaib’ (134) as he transforms from human to animal. Paul describes Leto as pacing like a caged animal (123) and we see Leto embrace his animality as he decides to rule with “eye and claw—as the hawk among lesser birds” (130). Leto is not an unjust man, but we do see his justice waning through the pressures of kanly and Arrakis. It does seem that his justice rebounds, however, and is on full display in the spice fields as he says “damn the spice” and saves his men from the voracious sandworm that eats the spiceharvester (154).

The only one we don’t see falter is Gurney Halleck, the valorous, and the only one left with Paul during the banquet scene after Leto is forced to leave to deal with the recovered carryall. Paul acts valorously at the banquet, but he is perhaps a bit too brash, like one whose valor is not tempered by wisdom, justice, and temperance?

There are at least two ways to think of Paul’s relation to the four personified virtues: psychologically/allegorically and practically.

Practically, we see that, in order for Paul to become a virtuous ruler, he’ll need to learn from his moral exemplars—three out of four of whom are failing to live up to their own ideal, leaving Paul to be potentially malformed, courageous but lopsided and discorded.

Psychologically/allegorically, we might see the four personifications of the cardinal virtues as aspects of Paul’s own psyche. I began thinking of the psychology of Paul and his four companions after reconsidering the Reverend Mother’s sententia. I was then reminded of Ursula K. Le Guin’s analysis of Frodo in her essay “Science Fiction and Mrs. Brown”:

“If you put Frodo together into one piece with Sam, and with Gollum, and with Smeagol—and they fit together into one piece—you get, indeed, a complex and fascinating character… so Tolkien in his wisdom broke Frodo into four: Frodo, Sam, Smeagol, and Gollum; perhaps five, counting Bilbo. Gollum is probably the best character in the book because he got two of the components, Smeagol and Gollum, or as Sam calls them, Slinker and Stinker. Frodo himself is only a quarter or a fifth of himself. Yet even so he is something new to fantasy: a vulnerable, limited, rather unpredictable hero, who finally fails at his own quest—fails it at the very end of it, and has to have it accomplished for him by his mortal enemy, Gollum, who is, however, his kinsman, his brother, in fact himself…” (The Language of the Night, 102-103)

Now is Le Guin totally right about Tolkien intentionally splintering the psyche of one character into four of five? I don’t know. But it seems reasonable to think that Frank Herbert might have, given that he’s making a reference to Plato’s Republic, which itself draws an analogy between, or is itself an allegory for the just society and the properly ordered psyche. Also, because Herbert is intentionally infusing Jungian psychology into his story both through appropriating Jungian archetypes and by using the collective unconscious as the main what-if of his story.

What does Paul need if he is to rule Arrakis (Plato’s Just city ‘Kallapolis’) well? He needs the world supporters, his father and mentors, who personify the four cardinal virtues.

What does Paul need if he is to rule his own self well? He must be virtuous: just, temperate, wise, and courageous—oh and throw in a bit of Stoic ataraxia and apatheia through the Litany Against Fear (fear is the mind killer…).

So, whether or not Paul is to become the ideal philosopher-king and everyone’s messiah, may depend heavily on what happens with his father and three mentors. But we need to wait and see. As of right now we’re left with Duke Leto, the Just, in the hands of the treacherous doctor Yueh.

Or consider buying me a coffee as a one-time thanks:

So, I just finished the battle between Jessica and Thufir, and it hit me. This whole book is one big bullfight. The bull and the matador change characters with each scene but … yea, one big bullfight. The impossible unbalancedness of power—never knowing who will be victorious: the bull or the matador.

The cardinal virtues piece is so funny because I'm just getting to this bit of Plato's Republic in my first ever read through, great timing.