"Hume's Arguments Against Miracles Fail -David Hume" - C.S. Lewis | Miracles Ch. 13

My Companion Essay Chapter 13 of CSL's Miracles

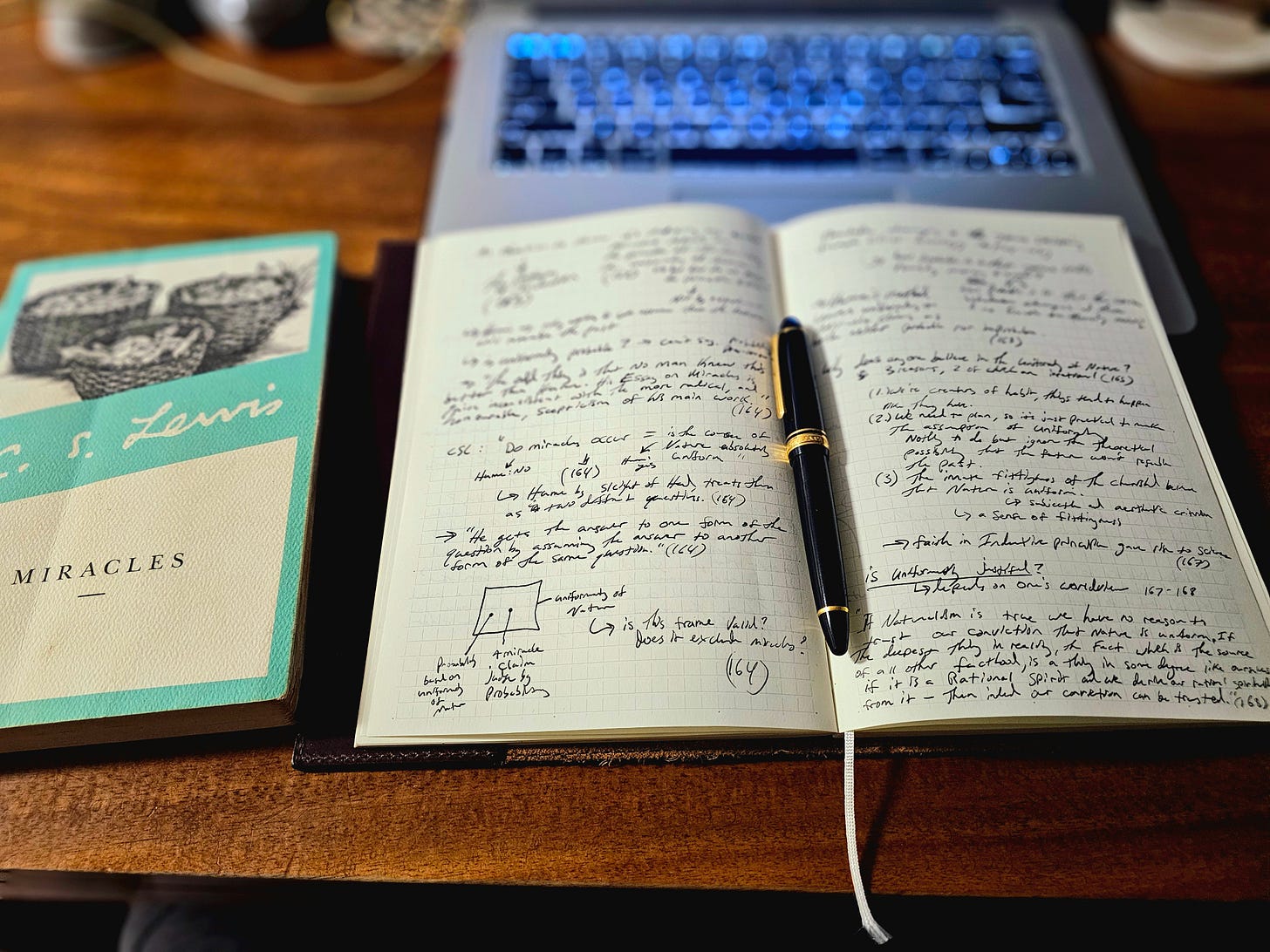

Welcome to the Parker’s Ponderings read-along of Miracles by C.S. Lewis. This is the sixth companion essay I’ve put out and in it I’ll be covering chapter 13 of the book. This essay was supposed to cover ch. 13 and ch. 14 but 14 is far too long. It demands it’s own essay—I definitely misjudged in my initial schedule. For the most part we’ve been keeping on track, but this has been much harder than I expected. I thought that since I know the book so well, it would be easy to write about it. It’s far worse because I have too much to say and never feel like I’m doing CSL justice. Anyways, chapter 14’s essay will be out later this week.

I’m committed to keeping these companion essays free but if you enjoy them consider becoming a paid subscriber to support my work or consider buying me a coffee to encourage me:

If you’re just discovering this read-along for the first time, you can catch up by reading companion essays below:

Essays on chapters 1&2, on chapter 3, on chapters 4-6, on chapters 7&8 on chapter’s 9-12

Here’s the read-along schedule again:

March 31st - Chapters 1-2 – World-and-life views, presuppositions, and the philosophy of fact

April 9th - Chapter 3 – Three Arguments from Reason Against Naturalism

April 11th – Chapters 4-6 – Four or Five More Arguments from Reason

Zoom Call for Paid Subscribers #1 – April 13th from 1:00pm – 2 or 2:30pm central

April 15th – Chapters 7-8 – common objections to miracles, the nature of nature, and what miracles are not

April 21st - Chapters 9-12 – The Author Analogy, The Ultimate Fact, Doctrine of God

Zoom Call for Paid Subscribers #2 – to be determined

May 7th-May 11th Chapter 13 and then Chapter 14 – Presuppositions and Argument from Reason revisited, Criterion of Miracles, a Theology of Religions

May 14thth – Chapters 15-Appendix B – The True Myth, One vs. Two-Floor Realities, Against Monism, Author Analogy Revisited

Zoom Call for Paid Subscribers #3 – to be determined

Chapter 13 – On Probability

So far in CSL’s preliminary study of miracles, he’s leveled a number of arguments against the idea that all miracle claims can be ruled out from the start. If CSL’s arguments go through, then miracles are possible in principle. But how do we determine if a miracle has actually happened? CSL acknowledges that maybe even most tales of the miraculous are just tall tales or flat out lies, but he claims that most stories about natural events are likewise false or highly embellished. So, what are we to do? How can we adjudicate whether or not a miracle claim is true? Well, we should accept the miraculous accounts which have sufficiently good evidence. Simple.

But how much evidence should we require to establish the miraculous? Well, how intrinsically probable is the story of the miracle? The less probable it is, the more evidence we should require to establish it. But then it looks like we’ll need a criterion of probability then as well. CSL says that the ordinary MO of the modern historian is to only admit of a miracle—if they think miracles are even possible at all—only after all naturalistic explanations have been tried and found inadequate for explaining the phenomena. But CSL argues that this procedure presupposes that every miracle is more improbable than even the most improbable natural event. But this is a presupposition brought to the inquiry—how does anyone know whether the most improbable natural event is more probable than the most probable supernatural one? Or if there are even a hierarchy of probable supernatural events and miracles?

CSL goes on to distinguish different kinds of ‘improbability’ in order to get clear on the kind that should actually impact miracle claims. He acknowledges that by definition, miracles are rare events—that’s the whole point of miracles—and as such, it is improbable that a miracle will occur at a particular time and place. But He argues that this kind of improbability doesn’t impact whether or not a miracle has happened. He gives an example of a pebble being dropped form the stratosphere. He argues that it is immensely improbable that the pebble will hit a particular spot. But when someone announces that the pebble has landed over here, the report is not incredible. Likewise, he notes that

When you consider the immense number of meetings and fertile unions between ancestors which were necessary in order that you should be born, you perceive that it was once immensely improbable that such a person as you should come to exist: but once you are here, the report of your existence is not in the least improbable. (161).

So this kind of “antecedent probability of chances” is not the kind of probability that matters in the miracle debate. Using past events or evidence to determine how likely a miracle is to occur doesn’t tell us about a particular miracle claim in view. Before the rock falling from the stratosphere lands, the chances that it will land on this particular spot are not high. But once you have the resting spot of the rock, the antecedent probability doesn’t matter.

CSL moves on to philosopher David Hume’s argument against miracles from intrinsic probability (163). CSL says that Hume rules out the plausibility of miracle claims by claiming himself that miracles are intrinsically improbable due to the uniformity of nature. Hume argued that a miracle is a violation of the laws of nature, but that the laws of nature have been established by firm and unalterable experience, and so from the very nature of the fact of the laws of nature, miracles are not rationally credible. No testimony can establish a miracle unless the falsehood of that testimony is more miraculous than the miracle claim it’s seeking to establish. And even in that case, Hume argues that the degree to which you can believe the claim to be true is what’s left over after subtracting the probability of the miraculous event from the probability that the miracle claim is false.[1]

CSL rightly notes that Hume’s probability argument against miracles depends on the principle of induction, i.e., that nature is uniform and that the future will resemble the past—CSL calls this the uniformity of nature or uniformity for short. But how do we know the uniformity of nature is veridical? Hume says the laws of nature, which depend on nature being uniform and the future resembling the past, are established by firm and unalterable experience. Buuut experience depends on the uniformity of nature, so we can’t use experience to establish uniformity, Mr. Hume. We haven’t experienced everything in the natural world. We haven’t observed the opposite side of the universe to know that uniformity rules there as well. How can experience helps us here? And sure, the past has been like the past, but how do we know that the future will be like the past? We haven’t observed the future.

Maybe we can we use probability to establish the uniformity of nature? Nope. CSL notes that probability likewise depends on or assumes the uniformity of nature. So that’s out too. And here’s the funny thing, David Hume is the one who made all of these arguments against the justification of the uniformity of nature popular! We now refer to this area of the philosophy of science as Hume’s ‘Problem of Induction’.[2] CSL says, “The odd thing is that no man knew this better than Hume. His Essay on Miracles is quite inconsistent with the more radical, and honorable, scepticism of his main work.” (164)

So, CSL accuses Hume of duplicity. Do miracles occur? Hume says “no, because of the uniformity of nature.” Meanwhile, Hume also argues that we have no good justification for believing that nature is uniform (the Problem of Induction). Which leads CSL to the conclusion that

By [Hume’s] method, therefore, we cannot say that uniformity is either probable or improbable; and equally we cannot say that miracles are either probable or improbable. We have impounded both uniformity and miracles in a sort of limbo where probability and improbability can never come. This result is equally disastrous for the scientist and the theologian; but along Hume’s lines there is nothing whatever to be done about it. (165).

CSL takes a break from blasting Hume with more Hume and gives us three reasons why people do believe in the uniformity of nature.

(1) We’re creatures of habit, things tend to happen like they have in the past.

(2) We need to plan, so it’s just practical to make the assumption of uniformity. There’s nothing to do but ignore the theoretical possibility that the future won’t resemble the past, that the laws of nature will turn on their respective heads in ten seconds from now.

(3) The innate fittingness of the cherished belief that nature is uniform. (165-66)

It’s (3) that CSL goes on to build up. It is fitting to have faith the uniformity of nature and when we do, look what happens! We get beautiful science that actually works. But CSL argues that not everyone just gets to have faith in induction—one’s worldview will determine whether or not the belief enjoys the fittingness required for acceptance. He claims that

If Naturalism is true we have no reason to trust our conviction that Nature is uniform. If the deepest thing in reality, the Fact which is the source of all other facthood, is a thing in some degree like ourselves—if it is a Rational Spirit and we derive our rational spirituality from it—then indeed our conviction can be trusted. (168).

But why think that? Well, because if God is the ultimate Fact, the Creator of our universe and of our rational minds, if He made us to reason in a similar fashion to Himself, to think His thoughts after Him, then we can trust that a God like that has made the universe uniform, has made it to operate under his set of rules, he is the law-giver of the laws of nature. The future will be like the past because He’s intended for us to live, and move, and reason, and have our being in a stable environment. And He’s created us to reason inductively as well as deductively and analogically and metaphorically and abductively and all the other ways we reason. If God exists, then we can have faith in the uniformity of nature, both ontologically—out there in the universe—and epistemologically/noologically—that is in our minds, in our cognitive faculties and belief forming processes. We can expect a high degree of fitness between our minds and the world we inhabit on theism.

CSL argues that on Naturalism, however, we have no rational designer of our cognitive faculties and no reason to believe that nature is in fact uniform now at the moment, nor that—even if it is uniform now—it will continue to be so 10 seconds from now. Is our faith in the uniformity of nature a thing we can trust on Naturalism? Or is it just the way that a mindless process of evolution has led us to prefer? Is it just how our minds happen to work?

So then, if you have God, then you can justify your faith in the principle of induction, or the uniformity of nature, but then you have no security against His special divine action, his bringing about miracles, “the philosophy which forbids you to make uniformity absolute is also the philosophy which offers you solid grounds for believing it to be general, to be almost absolute. the Being who threatens Nature’s claim to omnipotence confirms her in her lawful occasions.” (169).

CSL ends by giving us his criterion for judging miracles: fitness. Just as fittingness or fitness was used to justify a belief in the uniformity of nature, so too can it be used to adjudicate whether or not a miracle has happened. Can we give an analytic presentation of CSL’s criterion of fittingness? Well, no. CSL says that “Our ‘sense of fitness’ is too delicate and elusive a thing to submit to such treatment.” But he spends the next three chapters going over the central miracles of Christianity to show how the fit the fitness criterion, both to demonstrate how the criterion works and to help justify the examples.

[1] The plain consequence is (and it is a general maxim worthy of our attention), “That no testimony is sufficient to establish a miracle, unless the testimony be of such a kind, that its falsehood would be more miraculous, than the fact, which it endeavours to establish: And even in that case, there is a mutual destruction of arguments, and the superior only gives us an assurance suitable to that degree of force, which remains, after deducting the inferior.”

https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/miracles/#ArguAgaiMiraClai

[2] The original source of what has become known as the “problem of induction” is in Book 1, part iii, section 6 of A Treatise of Human Nature by David Hume, published in 1739 (Hume 1739). https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/induction-problem/

This book just keeps getting better and better. Thanks, Parker, for an exhilarating tour of a book that demonstrates so winsomely what it means to conform one's mind to Christ. The picture of Lewis tirelessly wielding a machete, chopping down very tall philosophical and theological weeds to give a clear view of the truth, came readily to mind as I read his arguments in this chapter.

Lewis's talk of historical evidence brought to mind N.T. Wright's excellent book, "The Resurrection Of The Son Of God." If, once you are convinced that miracles are possible, after reading Lewis, Wright's book is a magisterial study of the Gospels as history by a historian. It's long and detailed, but Wright is an enthusiastic exegete and writes well. Once I settled into it, I found it an exhilarating read.

Lewis's explanation of antecedent probability and the examples he gives (i.e., pebbles from the stratosphere and personal experiences) bring things to light that are so obvious they usually are unconsciously assumed, the truth of which, once brought to one's attention, is so startling as to provoke laughs of delight (p.161). It seems all of Lewis's books have such moments for me.

It seems to me that in refuting Hume, Lewis is going back to the Argument From Reason, especially as he begins to discuss the Uniformity of Nature (p.162)

On P. 168, at the bottom, where he is discussing Whitehead, is this what theologians call the Platonic-Christian synthesis?

I think, concerning Whitehead, it shows Lewis's magnanimity and deep confidence in what he believes to be true that he can find common ground with a thinker with whom he obviously has very deep disagreements. A good example for the rest of us.

Lewis's discussion of the Laws of Nature brings to mind Stephen Hawking's argument in "The Grand Design, " that the Laws of Nature are God, which goes to show you that even brilliant people can misunderstand what theists mean by God.

I love his comment at the top of p. 170 about Theology. I think one could say that behind all truths there is the Truth.

Also on p. 170, Lewis's "innate sense of the fitness of things" I think, is another expression of what one finds in "The Abolition of Man" and other places in Lewis's corpus: the idea that there is a baseline assumption that has to be accepted in order to reason at all.