The Explanatory Power of The Incarnation | C.S. Lewis's Miracles ch. 14

My Companion Essay

Welcome to the Parker’s Ponderings read-along of Miracles by C.S. Lewis. This is the seventh companion essay I’ve put out and in it I’ll be covering chapter 14 of the book.

The companion essay for chapters 15-the appendices will be out later this week, probably on Friday the 16th.

I’ve really enjoyed leading this read-along and book club, so I’ve decided to do a couple more. Right now I’m pretty much deadlocked between Dune by Frank Herbert and The Consolation of Philosophy by Boethius. Let me know which you’d prefer first. I am going to do both for sure. But right now I am just slightly be leaning towards Dune for June and half of July, then Consolation, then CSL’s Out of the Silent Planet in August. What do you think?

If you’re just discovering this read-along for the first time, you can catch up by reading companion essays below:

Essays on chapters 1&2, on chapter 3, on chapters 4-6, on chapters 7&8 on chapter’s 9-12, and chapter 13

Here’s the read-along schedule again:

March 31st - Chapters 1-2 – World-and-life views, presuppositions, and the philosophy of fact

April 9th - Chapter 3 – Three Arguments from Reason Against Naturalism

April 11th – Chapters 4-6 – Four or Five More Arguments from Reason

Zoom Call for Paid Subscribers #1 – April 13th from 1:00pm – 2 or 2:30pm central

April 15th – Chapters 7-8 – common objections to miracles, the nature of nature, and what miracles are not

April 21st - Chapters 9-12 – The Author Analogy, The Ultimate Fact, Doctrine of God

Zoom Call for Paid Subscribers #2 – to be determined

May 7th-May 11th Chapter 13

May 14th-Chapter 14 – a Theology of Religions and the Explanatory Power of the Incarnation

May 16thth – Chapters 15-Appendix B – The True Myth, One vs. Two-Floor Realities, Against Monism, Author Analogy Revisited

Zoom Call for Paid Subscribers #3 – May 17th at 2pm Central

Miracles ch. 14 – The Grand Miracle

“I believe in Christianity as I believe that the Sun has risen, not only because I see it, but because by it I see everything else.” (in The Weight of Glory, HarperOne, 140.)

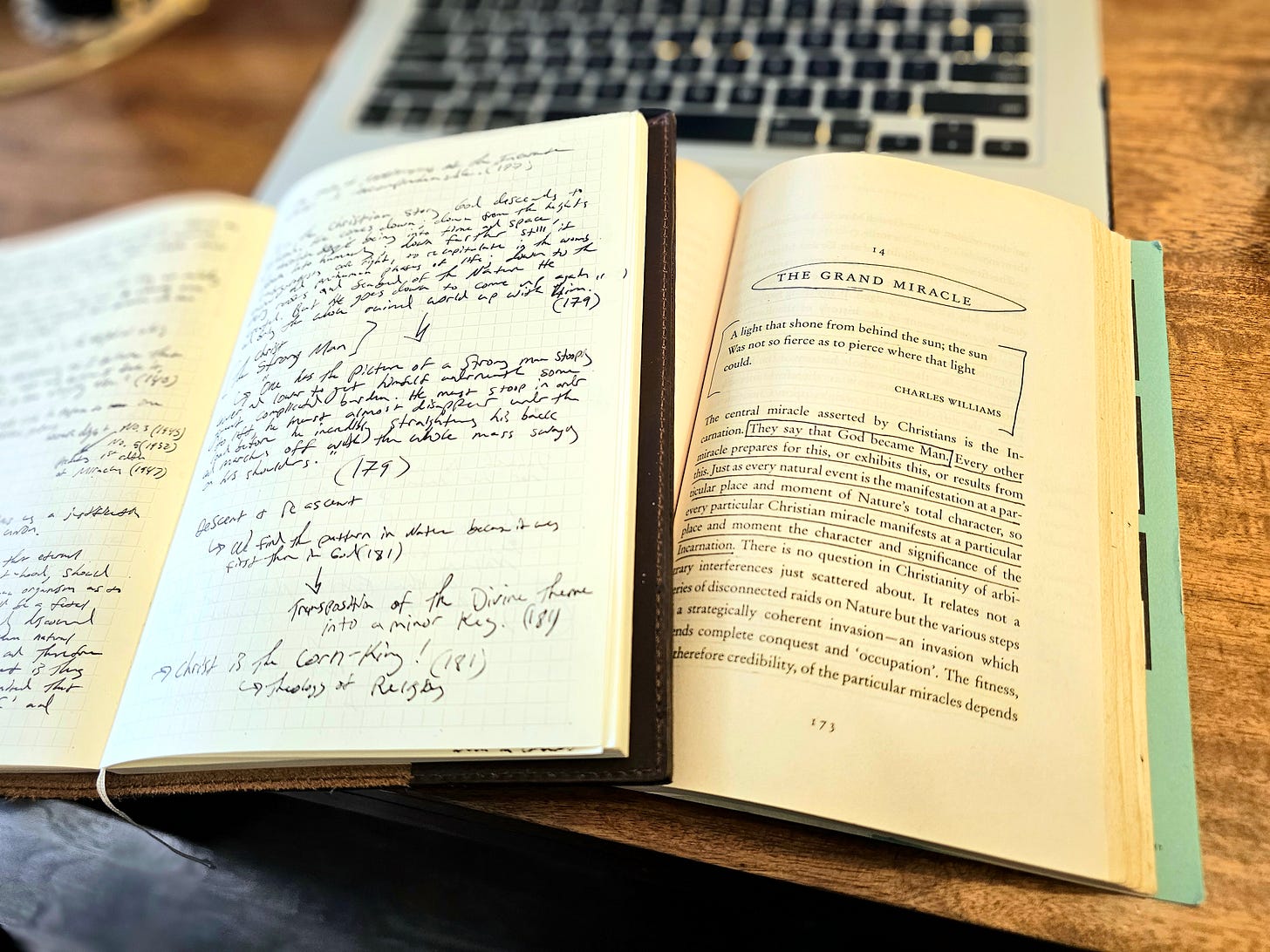

This companion essay for chapter 14 of CSL’s Miracles has taken me forever to write. The title of the chapter is “The Grand Miracle”, which is also the title of a sermon-turned-essay that CSL preached in 1945 but which is far more expanded in chapter 14. That is part of the reason it took me so long to write this companion essay—CSL packs a whole lot into this chapter!

I won’t cover everything from the chapter in detail—I can’t—but I will cover the things I found most interesting and I will leave it to you to add your favorite quotes and arguments from the chapter down below in the comments.

So, what does CSL take to be thee ‘Grand Miracle’? Well, the Incarnation of the Second Person of the Trinity, of course. God became man. A miracle which CSL argues was prepared for by every other miracle, or which every miracle exhibits, or which results from this one Grand Miracle. Miracles are about the incarnation of Christ—the enfleshing of the Son of God. In the incarnation, Christians believe that God came down from heaven and took on a human nature, that the eternal Son took on a second nature in addition to his divine nature, and in the person of Jesus Christ we find one person with two natures: one hypostasis: two ousias. This we call the ‘hypostatic union’ and this is CSL’s Grand Miracle.

It is in light of the Grand Miracle that we can judge other miracle claims as fitting or unfitting—think back to last chapter’s fitness criterion. If the story of Christianity is true, then the crux of the story of reality (pun intended, crux = cross ) is the incarnation, death and resurrection of Jesus. This is the miracle which all antecedent miracles have been pointing to and which all subsequent miracles refer back to. If a miracle claim is spurious, it won’t fit well within the Christian story and won’t cohere with the grand miracle.

Now this may seem too fast! How did we go from miracles generally conceived to a Christian criterion? Shouldn’t we take miracle claims on their own and build up a theory from there? Why assume Christianity is true and then judge miracle claims in light of it? Well, CSL continues on to argue for Christianity abductively, through a kind of inference to the best explanation. So he’s not merely assuming the truth of Christianity and poisoning the well against contrary miraculous claims, but instead leading us to his reasons for believing in Christianity through his criterion for judging miracle claims, which is the Grand Miracle.

So, why does CSL think Christianity and its Grand Miracle is true? He says that “the credibility [of the Incarnation] will depend on the extent to which the doctrine, if accepted, can illuminate and integrate that whole mass [of human knowledge].” (176). Here we see the abductive, almost transcendental reasoning. Even more explicitly, CSL says, “We believe that the Sun is in the sky at midday in summer not because we can clearly see the Sun (in fact we cannot) but because we can see everything else.” (176). This idea is something of a through line for CSL and harkens back to his 1945 essay, “Is Theology Poetry” wherein he says, “I believe in Christianity as I believe that the Sun has risen, not only because I see it, but because by it I see everything else.” (in The Weight of Glory, HarperOne, 140.)

So CSL takes an indirect approach to arguing for the truth of Christianity. He argues from the explanatory power of the Christian-world-and-life view, the truth of which hangs on the veracity of the Grand Miracle. If we assume the truth of Christianity, what follows? How much can we explain? CSL argues that this one miracle is like a lost chapter of the novel of history and with it in place, the rest of the story is further illuminated—it has a fitness that makes sense of everything else.

CSL acknowledges that it may strain a non-believer’s credulity to put the God-Man miracle at the center of one’s worldview—after all how could God become man at all? CSL argues that the conscious experience of Jesus Christ, one person with a divine and a human nature, is incomprehensible to us, it is nonetheless a justified mystery. How so? Well, yes bringing together a spiritual nature and a human nature seems pretty odd upon first glance, however, we shouldn’t sneer at this idea too much given that we ourselves are composite beings comprised of a material body and at least some immaterial aspect which is free from the laws of physics and can engage in logical reasoning and agent causation—which explains why he took so much time to advance his Arguments from Reason in chapters 1-6, and 13.

CSL goes on to describe the Incarnation in beautiful detail—the man truly had a way with words! He says that

In the Christian story God descends to reascend. He comes down; down from the heights of absolute being into time and space, down into humanity; down further still, if embryologists are right, to recapitulate in the womb ancient and pre-human phases of life; down to the very roots and seabed of the Nature He created. But he goes down to come up again and bring the whole ruined world up with Him. (179).

He continues on with one of my favorite analogies of the entire book:

“One has the picture of a strong man stooping lower and lower to get himself underneath some great complicated burden. He must stoop in order to lift, he must almost disappear under the load before he incredibly straightens his back and marches off with the whole mass swaying on his shoulders.” (179).

Jesus the strong man! He stooped down all the way to hoist all of creation on his shoulders so that he might drag the thing back up to glory. Fantastic! I always think of the Powerhouse Gym logo at this part of the book:

CSL then gives us a bit of a theology of religions, which is different from the philosophy of religion—i.e., that discipline which studies arguments for and against the existence of God (it may be a bad name for the discipline but it grew out of western philosophy and thus it focuses on arguments for and against monotheism), which itself should not be confused with ‘comparative religions’ which is the discipline of systematically comparing and contrasting different religions and their doctrines. A theology of religions, instead, is the discipline of explaining the phenomena of other religions in light of your own theology. If your theology is true, why are there rival conceptions of God? If your theology can’t account for rival conceptions, than it may be a mark against its explanatory power.

CSL’s theology of religions finds the pattern of descent and renascent in nature as the divine tune transposed into a minor key. Nature religions pick up on this minor key because it actually is out there in the world, but they emphasize it in different ways than intended partly because of the noetic effects of sin, that is that sin and corruption have marred every part of the human being, including our intellects. So proponents of rising and falling God build up their religion from the natural patter of the spring, summer, fall, and winter—with the planting, growing, and harvesting of the corn and other crops. But CSL says Christ is the true Corn-King,

The very thing which the Nature-religions are all about seems to have really happened once; but it happened in a circle where no trace of Nature-religion was present. It is as if you met the sea-serpent and found that it disbelieved in sea-serpents: as if history recorded a man who had done all the things attributed to Sir Launcelot but who had himself never apparently heard of chivalry. (183-184)

So the story of the dying and rising God happened once, not every season, but the religions which emphasize the descent and renascent are still hitting on a divine theme put into Nature by its Author in preparation for the true even, the Myth become Fact. This is why Protestant Christians emphasize the necessity of divine special revelation in the Bible. It is a corrective on our natural theology—lest we look to the female praying mantis and think God is someone who would cut the head off his beloved after coitus—or any number of other preposterous false steps.

CSL goes on to argue that the incarnation explains other natural phenomena like the vicariousness we find in nature, both good and ill. Like the parasite (bad) and the fetus (good), the cat sustaining itself on the mouse (bad) and the bees sustaining themselves on the flowers (good). From these examples he claims that “Nature has all the air of a good thing spoiled.” (196). The Christian story makes sense of the goodness and badness of nature, it was a good place corrupted by the fall of man—to which CSL gives a greater-good free will theodicy: there is evil in the world because God gave mankind volition, but God has not left us to our own devices, in redeeming humanity, He is making us into something more glorious than even unfallen humanity would have been and He has even redeemed death to be the vehicle to do so.

CSL give 3 attitudes on death:

1. The Stoic’s ‘Lofty’ Point of View on Death: regard death with indifference. It is natural and unavoidable. Don’t let it hamper you or impact your dispassionate march toward virtue.

2. The Natural Point of View on Death: Death is the greatest of all evils and ought to be fought at every turn.

3. The Christian Point of View on Death: On the one hand, Death is Satan’s triumph over humanity, it’s the punishment for the fall, and it’s the last enemy. On the other hand, Death is God’s great weapon, the thing Christ incarnated in order to conquer, as well as the means by which he conquered it. At the death of Christ, the author of life, death committed suicide.

CSL starts wrapping up the explanatory power argument with a pretty fantastic claim: the whole of Christian theology can be deduced from 2 facts:

a. That men make coarse jokes.

b. That men feel the dead to be uncanny (strange, mysterious, unsettling). (206-207)

From (a) CSL argues that an animal which finds its own animalness, or animality, funny or even objectionable, we see that there is an inherent quarrel between man the organism and man the spiritual being. We don’t find dogs thinking doginess is funny—they just embrace their doginess and splash around in mud puddles and roll on dead birds. From (b) CSL argues that we hate the possibility of corpses and ghosts because each is one half of the good thing: man. We are meant to be a soul-body composite, a psycho-somatic unity, and we find the division of the two detestable, grotesque, haunting. To which CSL says Christianity has the explanation. We are made in the image of God as embodied souls, yet we incurred the penalty for sins by misusing our God-given powers of volition, which is death, and so we die and the organism is parted from the enlivening spirit, which is horrific and detestable.

But thanks to the Incarnation, we find hope. We find the defeat of death in the death and resurrection of the God-Man.

Leave me your thoughts on this chapter in the comment section below. It’s definitely one of my favorite chapters, especially thanks to the Corn-King theology of religions bit.

Let me leave you with CSL’s own summary of the main point of the chapter:

Whether the thing really happened is a historical question. But when you turn to history, you will not demand for it that kind of degree of evidence which you would rightly demand for something intrinsically improbable; only that kind and degree which you demand for something which if accepted, illuminates and orders all other phenomena, explaining both our laughter and our logic, our fear of the dead and our knowledge that it is somehow good to die, and which at one stroke covers what multitudes of separate theories hardly cover for us if this is rejected. (212-213)

I learned a lot about christian theology in this chapter, for example the concept of vicariousness was finally consolidated out of things I sort of knew about the religion (I have never read the bible but grew up in a nominally christian society so have bits and pieces of it). The idea that the chosen people are so chosen to bear a heavy burden, for the vicariousness of the unchosen; just as Jesus is the ultimate source of vicariousness for all man. And it follows logically, some people are chosen, completely at random, to be the best athletes.

It was also quite a compelling point that Jesus was such a shrewd and demanding teacher but exhibited no signs of megalomania - indeed the Greek gods were rather megalomaniacal. From my limited knowledge it seems the apostles were also humble, and the early communes exhibited a complete disinterest in political power. This is certainly the kind of story that would lend itself to a usurpation of power, but it does not, because that's not the point - the point is the lifting up of man, the vicariousness, the forward march of Nature to be perfected over time.

This is great stuff, a whole new horizon has been opened up to me by this readalong. I can't wait to re-read Dune on here, and then finally read Boethius (Dune first plz, I would like to read some Augustine on my own before Boethius because I'm wild about chronology)

I agree. Lewis packs a great deal into this chapter; it seems like each succeeding chapter contains more ideas. In addition to his philosopher and theologian hats, in this chapter, Lewis dons his Scripture exegete and literary critic hats in making his arguments. It's all so rich, like seven-layer chocolate cake for the mind and spirit.

As Lewis points out, the Incarnation is the defining miracle of history. The very nature of reality changed. The early Christians understood this, but time tends to blunt human awareness, so it's good to have writers like Lewis to remind us of the true significance of God becoming man.

On p. 174, Lewis rehearses his famous Lord, Liar, Lunatic dictum, which I still think is a profound argument, although there has been a lot of pushback from certain quarters, as Lewis anticipates on the next page.

As Lewis points out, with certain questions, probabilities are useless. Fittedness then becomes a useful criterion for ascertaining the validity of a proposition.

On P. 176, in addition to the essay you mention, "Is Theology Poetry," I was reminded of another famous essay in God in the Dock, "Meditation In A Tool Shed," where the theme of the sun, as a metaphor for spiritual insight and revelation, is also used to great effect.

One could go on and on, but I was trying to think of a way Lewis's worldview could be summarized that would help explain why he goes to such lengths to be comprehensive with his explanations. I think one could say that Lewis believed that if a worldview was true and had explanatory power for any aspect of reality, then it should be able to explain all of reality. So he goes to work with all the tools he has to show how the incarnation is the ultimate explanation for reality as we know it.

As you say, Lewis had a way with words. I would go even further and say Lewis was one of the great prose stylists of the 20th century. Because of his education and work as a literary critic and historian, he spent his time analyzing and teaching the greatest English writers who ever lived, so he knew what great writing was. And he deliberately worked on being a great writer. He never learned to type; he wrote with a dip pen because he said he wanted to hear the rhythm of the words as he wrote.

I think it is this combination of exemplary prose stylist with his erudition and analytical thinking ability that truly puts him in a category by himself.

I'd still vote for Dune first, my copy is coming from Amazon today.